Why Most People Don't Survive John McCain's Brain Cancer

The Arizona senator is ending treatment for glioblastoma, a brain tumor he has battled for the past year.

Politics aside, you can’t deny that Senator John McCain knows what it’s like to put up a fight—as a Vietnam veteran (and prisoner-of-war survivor), active politician, and more recently, a father suffering from brain cancer.

McCain was diagnosed with an aggressive glioblastoma, a type of brain tumor, roughly one year ago. After undergoing a surgery to remove a blood clot above his eye, doctors discovered the presence of brain cancer in the 81-year-old Arizona senator.

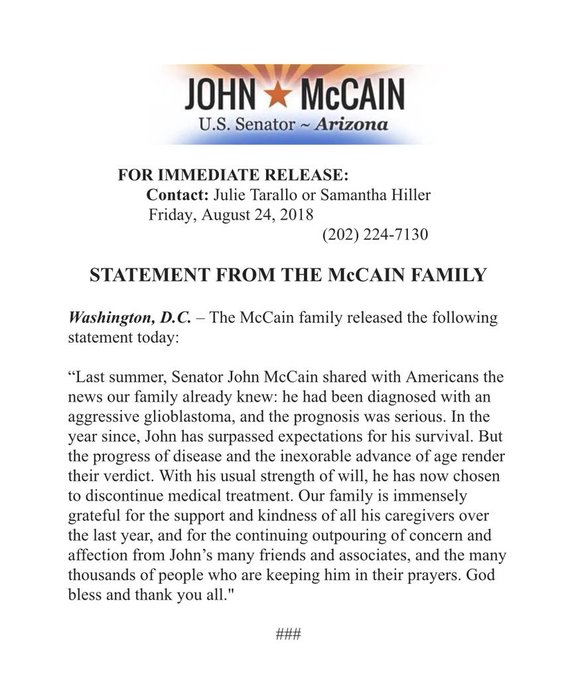

In an official statement released Friday, McCain’s family confirmed: “In the year since, John has surpassed expectations for his survival. But the progress of disease and the inexorable advance of age render their verdict. With his usual strength of will, he has now chosen to discontinue medical treatment.”

The American Cancer Society estimates that more than 23,000 cases of malignant brain or spinal cord tumors will be diagnosed this year. The overall chance of developing one during your lifetime is less than 1 percent—but 17,000 people will still die from it each year.

Glioblastomas are the most common malignant brain tumors in adults, says the ACS. Not only that, but they grow the fastest, making treatment especially tricky. But how exactly does this type of brain cancer strike? Can you spot the brain cancer symptoms before it becomes aggressive? Here, everything you need to know about glioblastomas and what the road to recovery actually entails.

What is a glioblastoma, exactly?

A glioblastoma is the most serious form of astrocytoma, a brain tumor that starts in glial cells known as astrocytes, or the star-shaped cells that make up the connective tissues of your brain, according to the American Brain Tumor Association. In fact, your brain is 90 percent glial cells, while the rest is made up of neurons, explains George Ansstas, MD, a Washington University neuro-oncologist and researcher specializing in brain tumors at Siteman Cancer Center in St. Louis.

“Unfortunately we don’t know exactly why it is so aggressive, but we do know it is aggressive in the course of the disease itself. Sometimes the tumor could double in size within 3 to 4 weeks,” says Dr. Ansstas.

What we do know: with glioblastomas, there are many tumor cells multiplying at a rapid pace—and they’re supported by lots of blood flow, since they can be found anywhere in your brain or spinal cord. The cells that set off the growth of this tumor are used to living within the brain, so it’s not difficult for them to thrive in that environment, according to the ABTA.

What causes glioblastoma?

So why do these cells become cancerous in the first place? Dr. Ansstas says that a variety of factors could cause them to become abnormal, like exposure to radiation and chemicals—which is particularly concerning, as veterans of the Vietnam War could have been exposed to these hazards during their time in service, according to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

But in a majority of patients, doctors are stumped as to why it even happens. From what they know, it’s not related to smoking or cell phone use (regardless of the headlines you read). Certain genetic conditions like Lynch syndrome or an underlying family history of brain cancer also seem to increase your risk, says Dr. Ansstas.

What are the symptoms of glioblastoma?

Back when McCain was first visiting with his doctor, he mentioned feeling fatigued, foggy, and having problems with his vision. After performing a CT scan, his doctor recommended coming back for an MRI.

Those types of symptoms aren’t uncommon with brain tumors, but they really vary depending on where the tumor is located, explains Dr. Ansstas. “If [the tumor] is in the frontal lobe, these patients could have cognitive and personality changes, while the occipital lobe might come with some visual symptoms,” he says. “If it’s in some other location obstructing the flow of the fluid in the brain, it can come with headaches.”

Older patients tend to be on the lookout for these problems, so it normally doesn’t take long to discover the brain tumor—the first presence of symptoms to diagnosis usually only takes a few weeks to a couple of months, says Dr. Ansstas. But in younger patients, the course of the disease can be a bit slower, and symptoms may be overlooked or mistaken for another health problem until they head to the doctor for a full-on evaluation.Seizures are also very common in people with glioblastoma, he adds. Other symptoms of glioblastoma to watch out for include nausea and vomiting, excessive tiredness, weakness, memory issues, or difficulty speaking.

How is glioblastoma treated?

Unfortunately there is no cure for glioblastoma, regardless of whether it’s aggressive or not. “The goal of the treatment is to prolong the patient’s life,” says Dr. Ansstas. “Even if the tumor was totally removed, there are still some dormant cells in the brain that would wake up at some point and the disease would come back.”

The go-to strategy involves surgical removal of the brain tumor, followed by a combination of radiation (the use of intense beams of energy waves or particles, like X-rays) and chemotherapy (a variety of drugs), which work together to attack cancer cells to impair their ability to divide, grow, and spread. Because glioblastoma is very complex and not yet fully understood, a variety of experts with specific specialties are needed to monitor treatment.

“The average survival is measured about 16 to 18 months for patients,” says Dr. Ansstas. “We’ve had patients who have lived beyond 7 years, but those are exceptional situations.”

So, why would you want the glioblastoma treatment to end as McCain has decided? It boils down to a couple of reasons, explains Dr. Ansstas. “Because the tumor is located in the brain, this translates to disability in one form or another, like paralysis, weakness, or cognitive issues,” he says. Second, the tools we have to treat this type of brain tumors are limited. Both the physician and patient have to work together to decide whether the treatment is truly beneficial.

There does seem to be a light at the end of the tunnel. “I believe the future of the disease is further understanding the molecular makeup of the tumor itself and the surrounding cells,” says Dr. Ansstas. “We think we’re on the right path, because current approaches in all cancers are becoming individualized in the era of immunotherapy. The future holds good promise for us.”

মন্তব্যসমূহ

একটি মন্তব্য পোস্ট করুন