Your body is immortal and you never even knew.

In the early 1900s it was perfectly normal for people to kick the bucket at age 50. These days, the average life expectancy in the US is around 80 years old, and centenarians — people who are 100 years or older — are becoming more and more common.

Now, science suggests that humans could — theoretically — live forever. A June 28 studyby a team of biologists at McGill University found there isn’t a detectable maximum life expectancy for humans.

The report was compiled after researchers analyzed data about the oldest people from the US, UK, France and Japan, for each year since 1968.

Scientists still aren’t sure what the age limit of a human might be, but data has shown that both maximum and average lifespans will continue to increase well into the future, says McGill biologist Siegfried Hekimi, who coauthored the study.

In fact, the number of centenarians is steadily increasing. In 2015, there were slightly more than 500,000 centenarians in the world. The United Nations predicts that by 2050 there could be over 3.5 million.

Super centenarians like Jeanne Calment of France — who died in 1997 at age 122 — have baffled scientists, leading them to wonder how long humans can really live.

A study published last October in the journal “Nature” suggested that the human lifespan hit its ceiling, maxing out around 115 years old. But this new data — and these badass super-centenarians — have proven otherwise.

The moral of the story? You should probably start saving for retirement. You may be around longer than you think.

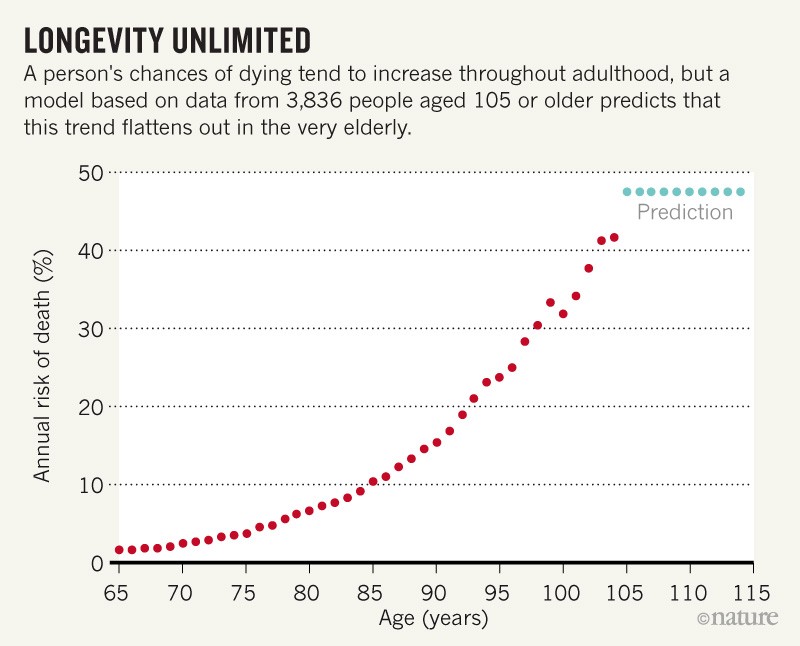

Good news for human life spans — at age 105, death rates suddenly stop going up ( COURTECY;-

Jeanne Louise Calment lived for 122 years and 164 days, the oldest verified age of any person, ever. Her interviews revealed a portrait of the centenarian in high spirits: “I've only ever had one wrinkle, and I'm sitting on it,” she told reporters when she turned 110. Calment died in 1997 in Arles, France, where she spent much of her impressively long life. No one else, according to accurate records, has lived beyond 120 years.

Whether there’s a limit to the human life span is an age-old question. An actuary named Benjamin Gompertz proposed in 1825 that mortality rates accelerate exponentially as we grow older. Under what is known as the Gompertz law, the odds of dying double every eight years. That seems to be the rule for people ages 30 to 80.

But researchers disagree about what happens to mortality rates very late in life. A new study, published Thursday in the journal Science, indicates that the Grim Reaper suddenly eases off the accelerator.

“The aim was to settle a controversy about whether human mortality has the same shape as mortality in many other species,” said study author Kenneth W. Wachter, professor emeritus of demography and statistics at the University of California at Berkeley. Mortality rates have been found to level off in lab animals, such as Mediterranean fruit flies and nematode worms. “We think we have settled it,” he said.

Mortality rates accelerate to age 80, decelerate and then plateau between ages 105 to 110, the study authors concluded. The Gompertz law, in this view, ends in a flat line.

To be very clear, we’re talking about the acceleration of mortality rates, not the odds themselves. Those still aren’t good. Only 2 in 100,000 women live to 110; for men, the chances of becoming a supercentenarian are 2 in 1,000,000. At age 105, according to the new study, the odds of surviving to your 106th birthday are in the ballpark of 50 percent. It's another 50-50 coin flip to 107, then again to 108, 109 and 110.

Led by Elisabetta Barbi at the Sapienza University of Rome and experts at the Italian National Institute of Statistics, the new research tracked everyone in Italy born between 1896 and 1910 who lived to 105 or beyond. The data included 3,836 people, of whom 3,373 were women and 463 were men. The national Italian registry, which requires yearly updates from citizens, provides more-accurate information than U.S. Social Security data. “Italy is likely to have the best data we have,” Wachter said.

Statistician Holger Rootzen at Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden called the study a “very careful and good analysis” that reveals a mortality plateau between ages 105 and 110.

Using similar longevity data from Japan and Western countries collected by the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research, Rootzen rejected the notion of a hard limit to human life in research published in December in the journal Extremes. He predicted it would be possible in the next quarter-century for someone to reach the age of 128.

Two years ago, researchers at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine argued in Nature, based on longevity data from 40 countries, for a maximum limit at around 115, as The Washington Post reported. In their view, Calment’s life span was a very lucky fluke.

Referring to the latest research, Brandon Milholland, who worked on the Nature study as a doctoral student, said that it was “highly unlikely” for mortality curves to level off so suddenly and flatly.

“There’s more than those two options,” Milholland said Wednesday. In a statement, his co-author Jan Vijg, a geneticist at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, called the choice between a sharp plateau or Gompertz law a “false dichotomy.”

“Their error bars are big,” Milholland said, which leaves room for steeper curves to arc through the Italian data. He agreed that the Gompertz law must end, because mortality rates cannot double beyond 100 percent. But this study has not convinced him that mortality rates stop increasing at around 50 percent.

Rootzen disputed the conclusions of the Nature paper estimating a limit on life span, saying the authors had made a statistical error: Yes, the odds of living beyond 115 are low, but that does not mean a limit exists, he said. He used the example of throwing darts at a dartboard. You might not get a bull's eye in 10 throws. Toss thousands of darts at a dartboard, though, and maybe you will.

“They just don't understand this problem that if you make more trials” — more darts at the dartboard or more people living to very old ages — “then the record becomes higher,” Rootzen said.

The numbers of the very old are growing. In Italy, for example, four people born in 1896 lived to 105 or beyond. More than 600 people born in 1910 lived as long. Between 1896 and 1910, infant mortality in Italy lessened, Wachter said. In later decades, the care of 80- and 90-year-olds improved, too, welcoming more people into the centenarian ranks.

“When we understand the interactions between our genomic heritage and all these other well-studied practical factors like nutrition and behavior, we are going to understand why people are able to make this progress to the 80s and 90s and extend it,” he said.

So far, the very oldest among us have emerged from all walks of life. “The lifestyle recommendations — you exercise, you eat this or that — these are quite effective at younger ages but don’t seem to play a role at older ages,” Rootzen said.

Calment said she smoked two cigarettes a day until she was 119 and only then kicked the habit because she couldn't see well enough to light up.

Is There a Limit to the Human Life Span? ( COURTECY

Is There a Limit to the Human Life Span? ( COURTECY

The average human life span has continued to increase. Will humans ever reach a limit to how long we can live?

Credit: Grigvovan/Shutterstock

There may be no limit to how long humans can live, or at least no limit that anyone has found yet, contrary to a suggestion some scientists made last year, five new studies suggest.

In April, Emma Morano, the oldest known human in the world at the time, passed away at the age of 117. Supercentenarians — people older than 110 — such as Morano and Jeanne Calment of France, who died at the record-setting age of 122 in 1997, have led scientists to wonder just how long humans can live. They refer to this concept as maximum life span.

In a study published in October in the journal Nature, Jan Vijg, a molecular geneticist at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York, and his colleagues concluded that humans may have reached their maximum life span. They analyzed multiple databases containing data on how long people have lived in recent decades in many countries and found that survival rates among the oldest people in most countries had not changed since about 1980. They argued that the human maximum reported age at death had apparently generally plateaued at about 115. [Extending Life: 7 Ways to Live Past 100]

However, the findings of five new studies now strongly disagree with this prior work. "I was outraged that Nature, a journal I highly respect, would publish such a travesty," said James Vaupel, a demographer at the Max Planck Odense Center on the Biodemography of Aging in Denmark. Vaupel co-founded the International Database on Longevity, one of the databases analyzed in the previous study.

Vaupel argued that the prior work relied on an outdated version of the Gerontology Research Group's database "that lacked data for many of the years they studied. Furthermore, they analyzed maximum age at death in a year, rather than the more appropriate maximum life span attained in a year — in many years, the world’s world's oldest living person was older than the oldest person who died that year," he told Live Science. "If appropriate data from the Gerontology Research Group are used, then ... there is no sign of a looming limit to human life spans."

Siegfried Hekimi, a geneticist at McGill University in Montreal, and his colleagues similarly found no evidence that maximum human life span has stopped increasing. By analyzing trends in the life spans of the longest-living individuals from the United States, the United Kingdom, France and Japan for each year since 1968, they found that both maximum and average life spans may continue to increase far into the foreseeable future.

Maarten Rozing, a gerontology researcher at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark, and his colleagues said the authors of the previous study committed errors in their statistical analyses. "We think that the claim that human life span has reached its limit should be regarded with caution," Rozing told Live Science. "Overall taken, there are very strong arguments to believe that our life span is still increasing, and, as long as our living conditions keep on improving, there is no reason to believe that this will come to a halt in the future." [7 Ways the Mind and Body Change with Age]

Similarly, in an analysis of Japanese women, who make up a growing number of centenarians, or people over 100, Joop de Beer, a demographer at the Netherlands Interdisciplinary Demographic Institute, and his colleagues suggested that the maximum human life span may increase to 125 years by 2070. "There is no reason to expect that a limit to human life span is in sight," de Beer told Live Science. He added that two kind of criticisms can be made about the prior work: "They did not apply their method correctly," and "they did not apply the correct method."

But the researchers did caution that, although the prior work might not have presented a strong argument for a limit to maximum human life span, it does not mean such a limit does not exist. "The evidence is mixed, but at present, the balance of the evidence suggests that if there is a limit, it is above 120, perhaps much above, and perhaps there is not a limit at all," Vaupel said. "Whether or not there is a looming limit is an important scientific question."

"Average human life span is clearly increasing continuously," Hekimi said. "The failure to identify a current limit to maximum human life span suggests that the increase in average life span might continue for quite a while."

Vijg defended his team's October study. "We agree with none of the arguments put forward — sometimes because they were based on a misunderstanding, sometimes because they were plain wrong, and sometimes because we disagreed with the arguments themselves," he told Live Science.

Jay Olshansky, a biodemographer at the University of Illinois at Chicago who did not take part in either the previous work or the new studies, found the rebuttals "a bit amusing." He said the key problem with all of these arguments about maximum human life span is that, of the 108 billion or so humans ever born, "only a handful have ever lived to extreme old age beyond age 110, and it's only in recent times that the number of centenarians has risen."

"The rebuttals are mostly focused on slightly different ways of looking at the same limited data," Olshansky said. "Basically, if you tilt your head a little to the left or right and look at the same old age mortality or survival statistics for all humans, you might come to slightly different conclusions."

Future research should analyze the statistics of human aging as well as the human genome, which "will tell us whether people that have particularly long lives have a particular genetic makeup and whether this makeup changes with changes in the average life span," Hekimi said. "Carrying out such studies and finding out will take a while."

The five new studies are detailed online June 28 in the journal Nature.

Original article on Live Science.

মন্তব্যসমূহ

একটি মন্তব্য পোস্ট করুন