More Young Adults Getting, Dying From Colon Cancer

May 10, 2018 -- Heather Blackburn-Beel was 34 years old when the pain in her belly started. The Indiana resident was diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome, and the mother of two and full-time nurse felt that made sense with her busy and stressful schedule.

But her mother, Kaye Blackburn, wasn’t convinced. Colon cancer runs in the family, and it had claimed the lives of many relatives, including Kaye’s older brother at age 32. She didn’t want her daughter to take any chances.

Kaye says she begged her daughter to get a colonoscopy, even offering to pay for it. But Heather didn’t feel that she had the time or that anyone needed to spend money on it. She finally relented when the pain worsened over several months, but by then, her mother’s worst fear had come true. Heather was diagnosed with stage IV colon cancer. Her colon was removed and she began chemotherapy, but the cancer had already spread to other parts of her body.

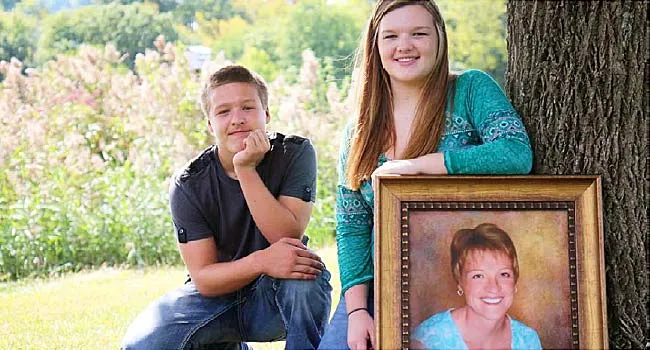

“I think her biggest concern was for her children. She wanted to live to see them. Her goal was to see them through high school,” Kaye says, pausing with heavy sadness in her voice. “But that didn’t happen.”

Heather died on May 23, 2014, after a 4 1/2-year battle against the disease. The 38-year-old is survived by a large family that includes her husband, two teenage children, mother, father, and two sisters.

“I think it’s probably the worst loss that anyone can have. I don’t think there is anything that prepares you. It’s not natural,” Kaye says. “You never get over losing a child. You just never do. You deal with it. You live with it. But you still have a lot of bad days where you miss her terribly.”

Rising Rates of Colon Cancer in Young People

Heather’s death is part of a concerning trend: More young adults are being diagnosed with colorectal cancer, and more are dying.

Because getting tested is key to prevention, the American Cancer Society is expected to release updated screening guidelines in 2018. “We are not at liberty to provide any details regarding the new CRC [colorectal cancer] screening guidelines until they are published, which should be sometime this year,” says Rebecca Siegel, strategic director of surveillance information services at the agency.

For now, 50 remains the recommended screening age for most, although the American College of Gastroenterology says African-Americans should start routine screening at 45 because they have higher odds of getting colorectal cancer than whites. Anyone with a family history is also supposed to get tested starting at age 40.

Colorectal cancer is the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the U.S. While the death rate for young adults is small, it is on the rise. Last year, the American Cancer Society published a study finding a 1.4% annual increase in death rates for colorectal cancers for adults under 55 between 2004 and 2014. That increase only applied to white adults.

An earlier study from the group showed that between 1974 and 2013, colon cancer diagnoses increased by 1% to 2% per year among people between the ages of 20 and 39, and by .5% to 1% per year for those between the ages of 40 and 54. Rectal cancer rates have been increasing even longer and faster, rising about 3% annually since the 1970s and 1980s among those between ages 20 and 39. The study did not look at race or sex.

“One of the things we’ve been trying to do with these papers is to increase awareness. There are a lot of delays in diagnosis for young people because their doctors aren’t thinking cancer when a 20-year-old says their stomachis hurting and they have rectal bleeding,” Siegel says.

A recent study found that it took 217 days after they first had symptoms for someone under the age of 50 to get treatment for rectal cancer. That compared with just 30 days for those over 50.

“We have to get rid of the old concept and old idea that young people don’t get cancer. We have to believe and understand that they can,” says Felice H. Schnoll-Sussman, MD, director of the Jay Monahan Center for Gastrointestinal Health at New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City. It’s named after broadcaster Katie Couric’s late husband, who died of colon cancer at age 42.

“This age of 50 that was chosen for starting colorectal screening, there is nothing magical about it. We had to decide upon an age, and the rationale is 10 years before the average age of diagnosis. But what’s the difference between a 49-year-old and a 50-year-old? Nothing,” Schnoll-Sussman says.

Lisa Johnson is well aware of that bias toward young people. She has no family history of colorectal cancer. So when the 26-years old from Rivesville, WV, first had constipation, bloating, and cramping, urgent care clinics kept telling her it was hemorrhoids.

She lived with the symptoms for several months until she got an unrelenting, stabbing pain in her right buttock. That’s when she sought out more specialized help. A surgeon found a tumor about 7 centimeters (2.75 inches) long blocking 90% of her rectum, and her colon cancer diagnosis came quickly after that.

“I have lost way too many friends in their 20s because people say screening shouldn’t start until 50 or their insurance won’t pay for it because the guideline says 50. Everyone I meet that is my age or in their 30s when diagnosed, we all have the same story.

“We had doctors who didn’t take us seriously, and we had to fight to get to a doctor who understood that something wasn’t right,” Johnson says. “If I walked into a doctor’s office in my 20s and said I found a lump on my breast, a doctor would never say, ‘Ah, you are 25, don’t worry. You’re too young for it to be cancer.’ But that’s happening all the time for patients with colon cancer.”

Cracking the Mystery

While researchers can clearly see a rise in colorectal cancer diagnoses and mortality rates in young people, they don’t know what’s driving it.

“It bothers me on a daily basis,” Siegel says.

By 2030, colorectal cancer incidence rates will be up 90% in people between ages 20 and 34, and 28% for people between ages 35 and 49.

Lack of exercise, diet, obesity, smoking, and alcohol can raise the odds of having colon cancer at all ages, and researchers are looking at all for potential causes. Siegel says she thinks there could also be a connection to the body's microbiome -- the bacteria that build up in our gut and are influenced by a wide variety of things in our diet and environment.

Researchers says some clues are starting to emerge, showing differences in the disease in younger people. It’s most commonly found on the left side of the colon or in the rectum. Some studies show that younger people have more aggressive cancer with worse prognoses. The disease is generally more advanced -- stage III or IV -- in younger people, perhaps a reflection of the challenge in getting diagnosed when you're younger than 50.

“Money needs to be put into this research because there are undoubtedly genes we have not found. This is only going to become more clear if we have research funds to try to figure it out. The answers are out there. We just don’t know them yet,” Schnoll-Sussman says.

The Power of Prevention

Siegel says the American Cancer Society is determined to raise awareness of colorectal cancer and improve its diagnosis. Ninety percent of people diagnosed at an early stage survive beyond 5 years, compared with an 11% survival rate after 5 years with the late-stage disease.

“We need to really talk about the symptoms. No matter how old you are, if you have these symptoms and they are persisting, go to your doctor and get it checked out. It probably isn’t cancer, but it could be,” she says.

Doctors say the most common symptoms of colorectal cancer in young patients are:

- Blood in the stool

- Bleeding from the rectum

- Abdominal cramping

Young patients may also see a difference in the shape of their stool and the frequency or difficulty with bowel movements.

Many mutations, or changes in genes, are associated with a higher chance of having colorectal cancer, and people who have those changes do often get diagnosed at an early age. But the majority of cases are sporadic, meaning there is no known cause.

Knowing your family history is important. The general population has a 2% lifetime risk of getting colorectal cancer. That goes up to over 80% for people with the inherited Lynch syndrome and 100% for familial adenomatous polyposis or FAP, both genetic mutations

Eduardo Vilar-Sanchez, MD, PhD, an assistant professor in the Department of Clinical Cancer Prevention at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, did a study on his own hospital’s population that found one-third of colorectal cancers diagnosed before the age 35 are hereditary.

“I would interpret this for doctors or medical oncologists as saying that every time we see a patient that is young with colorectal malignancy, we must think about hereditary syndrome,” he says. “For a third of the patients, we should be referring all these people for genetic counseling. The management isn’t going to change for them, but there will be implications for family members.”

Heather Blackburn-Beel’s family is one of many who didn’t know Lynch syndrome ran in their family until Heather’s doctor recommended genetic testing and found she had it. Now the family understands why so many aunts, uncles, and cousins through the years have been diagnosed with, and died from, colon and stomach cancers.

Since Heather’s diagnosis, surviving family members have gotten serious about regular colonoscopies long before the recommended age of 50. Her children, for example, will start when they are 20 and get one every year. “If something happens, they’re going to know about it and be able to get ahead of it,” Kaye says.

Colonoscopies are generally the preferred screening method, and studies show they cut the odds of death by about 50%. They look at the rectum and entire colon.

Other approved methods include:

- Sigmoidoscopies. These look at the rectum and part of the colon. If no polyps are found, these tests are generally repeated every 10 years

- .Stool tests that detect blood in fecal matter. Studies show they can lower the number of colorectal cancer deaths by 15% to 33% in people ages 50 to 80 when done every 1 to 2 years.

- Stool DNA test. Cologuard is currently the only FDA-approved test. This is a new test, so the benefits and harms are less well-established than for other tests.

Moving Forward

Vilar-Sanchez says managing young colorectal cancer patients requires a different approach than for patients over 50. He says his hospital started making this shift in treatment about 2 years ago.

“The expertise of a multidisciplinary team is needed, including genetic counselors, geneticists, fertility doctors, and psychological support, because being diagnosed at that age is a shock,” he says. “The best message we can get out there is young patients have their own issues, and it’s very important to recognize those.”

He also says that colorectal cancer in young people tends to be more aggressive and may need to be treated differently.

Johnson can speak to the impact a colorectal cancer diagnosis has had on her life. She was a recent college graduate, a newlywed, and worked as a dance teacher when she was diagnosed at 26. While her friends were getting married and buying houses, she had multiple surgeries, got chemotherapy and radiation, and had to give up her job.

Now 34, she is in remission but lives with an ostomy bag. She is unable to have children because she had a complete hysterectomy and says she and her husband now focus their devotion on their nieces, nephews, and dogs. Still, she’s grateful to be alive and is working now to figure out what comes next.

“I’ve had to say goodbye to my old body. I have a new one now. This one saved my life, and I will embrace it. But the fight after the fight has been challenging. I felt like I became a really good professional cancer patient and often wonder: Now what,” Johnson says. “I think my goal now is to keep telling people my story. I didn’t listen to my body for a very long time, and I want to keep others from making that same mistake.”

Many doctors and patients also agree that doctors also need to be better educated about symptoms, no matter the age of the patient.

“I kind of blame some of the doctors who put Heather off, probably for a good 6 months to a year,” says Kaye Blackburn, now 66 years old. “It sounds cliché, but if I can help someone else avoid what we have been through, then I will do it. It was just so horrible for Heather and her kids and our whole family.

“So if you have symptoms, get them checked. If you don’t think the doctor knows what they’re talking about, find another doctor. And if you have a family history of colon cancer, you definitely need to be screened. Don’t wait until it’s too late.”

মন্তব্যসমূহ

একটি মন্তব্য পোস্ট করুন