HISTORY of rohingya people , MIGRATED PEOPLE AND and original history of rohingya state of miyanmer ( from wikapedia )

Rohingya people

| Ruáingga ရိုဟင်ဂျာ | |

|---|---|

| |

| Total population | |

| 1,547,778[1]–2,000,000+[2] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Myanmar (Rakhine State), Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Nepal, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Thailand | |

| 1.0[3]–1.3 million[4][5][6] | |

| 400,000[7] | |

| 300,000–500,000[8][9][10] | |

| 200,000[11][12][13] | |

| 100,000[14] | |

| 40,070[15] | |

| 40,000[16][17] | |

| 11,941[18] | |

| 200[19] | |

| Languages | |

| Rohingya | |

| Religion | |

| Islam | |

| Islam by country |

|---|

|

The Rohingya people (/ˈroʊɪndʒə/, /ˈroʊhɪndʒə/, /ˈroʊɪŋjə/, or /ˈroʊhɪŋjə/)[20] are Muslim Indo-Aryan peoples from the Rakhine State, Myanmar.[1][21][22]

According to the Rohingyas and some scholars, they are indigenous to Rakhine State, while other historians claim that the group represents a mixture of precolonial and colonial immigrations. The official stance of the Myanmar government, however, has been that the Rohingyas are mainly illegal immigrants who migrated into Arakan following Burmese independence in 1948 or after the Bangladesh liberation war in 1971.[23][24][25][26][27][28][5][29]

Muslims have settled in Rakhine State (also known as Arakan) since the 15th century, although the number of Muslim settlers before British rule is unclear.[30] Despite debates concerning its origins,[24] the term "Rohingya," in the form of Rooinga, first appeared in 1799 in an article about a language spoken by Muslims claiming to be natives of Arakan. In 1826, after the First Anglo-Burmese War, the British annexed Arakan and encouraged migrations from Bengal to work as farm laborers. The Muslim population may have constituted 5% of Arakan's population by 1869, although estimates for earlier years give higher numbers. Successive British censuses of 1872 and 1911 recorded an increase in Muslim population from 58,255 to 178,647 in Akyab District. During World War II, the Arakan massacres in 1942 involved communal violence between British-armed V Force Rohingya recruits and Buddhist Rakhine people and the region became increasingly ethnically polarized.[31] After Burmese independence in 1948, the mujahideen rebellion began as a separatist movement to merge the region into the East Pakistan and continued into the 1960s, along with the Arkanese Independence Movement by Rakhine Buddhists. The rebellion left enduring mistrust and hostilities in both Muslim and Buddhist communities. In 1982, General Ne Win's government enacted the Burmese nationality law, which denied Rohingya citizenship, rendering a majority of Rohingya population stateless.[1] Since the 1990s, the term "Rohingya" has increased in usage among Rohingya communities.[24][29]

Prior to the 2015 Rohingya refugee crisis and the military crackdown in 2016 and 2017, the Rohingya population in Myanmar was around 1.1 to 1.3 million[4][5][6][1][4] They reside mainly in the northern Rakhine townships, where they form 80–98% of the population.[29] Many Rohingyas have fled to neighbouring Bangladesh,[32] to areas along the border with Thailand, and to the Pakistani city of Karachi.[33] More than 100,000 Rohingyas in Myanmar live in camps for internally displaced persons, not allowed by authorities to leave.[34][35] Probes by the UN have found evidence of increasing incitement of hatred and religious intolerance by "ultra-nationalist Buddhists" against Rohingyas while the Burmese security forces have been conducting "summary executions, enforced disappearances, arbitrary arrests and detention, torture and ill-treatment and forced labour" against the community.[36] International media and human rights organizations have often described Rohingyas as one of the most persecuted minorities in the world.[37][38][39]According to the United Nations, the human rights violations against Rohingyas could be termed as "crimes against humanity".[36][40] Rohingyas have received international attention in the wake of the 2012 Rakhine State riots, the 2015 Rohingya refugee crisis, and the 2016–17 military crackdown.

Nomenclature

The Rohingya refer to themselves as Ruáingga /ɾuájŋɡa/. In the dominant languages of the region, they are known as rui hang gya (following the MLCTS) in Burmese: ရိုဟင်ဂျာ /ɹòhɪ̀ɴd͡ʑà/ and Rohingga in Bengali: রোহিঙ্গা /ɹohiŋɡa/. The term "Rohingya" comes from Rakhanga or Roshanga, the words for the state of Arakan.[41][42]

Jacques P. Leider states that in precolonial sources, the term Rohingya, in the form of Rooinga appears in a text written by Francis Buchanan-Hamilton.[43][44] In his 1799 article "A Comparative Vocabulary of Some of the Languages Spoken in the Burma Empire", Hamilton stated: "I shall now add three dialects, spoken in the Burma Empire, but evidently derived from the language of the Hindu nation. The first is that spoken by the Mohammedans, who have long settled in Arakan, and who call themselves Rooinga, or natives of Arakan."[43] The word Rohingya means "inhabitant of Rohang", which was the early Muslim name for Arakan.[45] Historian Aye Chan from Kanda University of International Studies states that though Mulims have lived long in Arakan, the term Rohingya was created by descendants of Bengalis in the 1950s who had migrated into Arakan during colonial times. He also says the term cannot be found in any historical source in any language before the 1950s.[46]

After riots in 2012, academic authors used the term Rohingya to refer to the Muslim community in northern Rakhine. Professor Andrew Selth of Griffith University for example, uses "Rohingya" but states "These are Bengali Muslims who live in Arakan State...most Rohingyas arrived with the British colonialists in the 19th and 20th centuries."[23][25] Among the overseas Rohingya community, the term has been gaining popularity since the 1990s, though a considerable portion of Muslims in northern Rakhine are unfamiliar with the term and prefer to use alternatives.[24][44]

History

Although Muslim settlements have existed for a long time in Arakan, the number of original settlers before the British rule are generally assumed to be low.[47] After four decades of British rule in 1869, Muslim settlers reached 5% of Arakan's population. The number steadily increased until World War II.[29]

Kingdom of Mrauk U

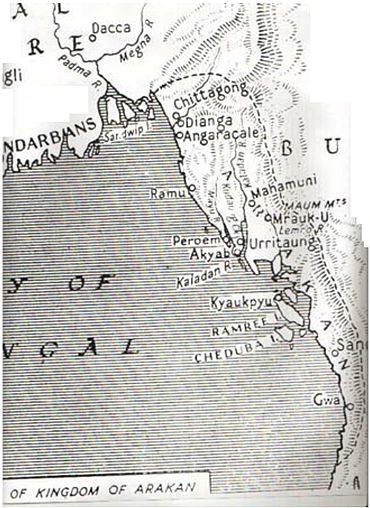

Early evidence of Bengali Muslim settlements in Arakan date back to the time of Min Saw Mon (1430–34) of the Kingdom of Mrauk U. After 24 years of exile in Bengal, he regained control of the Arakanese throne in 1430 with military assistance from the Bengal Sultanate. The Bengalis who came with him formed their own settlements in the region.[48][49]

Min Saw Mon ceded some territory to the Sultan of Bengal and recognised his sovereignty over the areas. In recognition of his kingdom's vassal status, the kings of Arakan received Islamic titles and used the Bengali gold dinar within the kingdom. Min Saw Mon minted his own coins with the Burmese alphabet on one side and the Persian alphabet on the other.[49]

Arakan's vassalage to Bengal was brief. After Sultan Jalaluddin Muhammad Shah's death in 1433, Narameikhla's successors invaded Bengal and occupied Ramu in 1437 and Chittagong in 1459. Arakan would hold Chittagong until 1666.[50][51]

Even after gaining independence from the Sultans of Bengal, the Arakanese kings continued the custom of maintaining Muslim titles.[52] The Buddhist kings compared themselves to Sultans and fashioned themselves after Mughal rulers. They also continued to employ Muslims in prestigious positions within the royal administration.[53] The Bengali Muslim population increased in the 17th century, as they were employed in a variety of workforces in Arakan. Some of them worked as Bengali, Persian and Arabic scribes in the Arakanese courts, which, despite remaining Buddhist, adopted Islamic fashions from the neighbouring Bengal Sultanate.[53] The Kamein, who are regarded as one of the official ethnic groups of Myanmar, are descended from these Muslims.[54] Also during the 17th century, tens of thousands of Bengali Muslims were captured by Arakanese raiders—with some serving in the king's army, others sold as slaves and others forced to settle in Arakan.[45]

Burmese conquest

Following the Konbaung Dynasty's conquest of Arakan in 1785, as many as 35,000 Rakhine people fled to the neighbouring Chittagong region of British Bengal in 1799 to escape persecution by the Bamar and to seek protection under the British Raj.[55] The Bamar executed thousands of Rakhine men and deported a considerable portion of the Rakhine population to central Burma, leaving Arakan as a scarcely populated area by the time the British occupied it.[56]

According to an article on the "Burma Empire" published by the British Francis Buchanan-Hamilton in 1799, "the Mohammedans, who have long settled in Arakan", "call themselves Rooinga, or natives of Arakan."[43] However, according to Derek Tokin, Hamilton no longer used the term to refer to the Muslims in Arakan in his later publications.[24] Sir Henry Yule saw many Muslims serving as eunuchs in Konbaung while on a diplomatic mission to the Burmese capital, Ava.[57][58]

British colonial rule

British policy encouraged Bengali inhabitants from adjacent regions to migrate into the then lightly populated and fertile valleys of Arakan as farm laborers. The East India Company extended the Bengal Presidency to Arakan. There was no international boundary between Bengal and Arakan and no restrictions on migration between the regions. In the early 19th century, thousands of Bengalis from the Chittagong region settled in Arakan seeking work.[59]

The British census of 1872 reported 58,255 Muslims in Akyab District. By 1911, the Muslim population had increased to 178,647.[60] The waves of migration were primarily due to the requirement of cheap labour from British India to work in the paddy fields. Immigrants from Bengal, mainly from the Chittagong region, "moved en masse into western townships of Arakan". To be sure, Indian immigration to Burma was a nationwide phenomenon, not just restricted to Arakan.[61]

Historian Thant Myint-U writes: "At the beginning of the 20th century, Indians were arriving in Burma at the rate of no less than a quarter million per year. The numbers rose steadily until the peak year of 1927, immigration reached 480,000 people, with Rangoon exceeding New York City as the greatest immigration port in the world. This was out of a total population of only 13 million; it was equivalent to the United Kingdom today taking 2 million people a year." By then, in most of the largest cities in Burma, Yangon, Sittwe, Pathein and Mawlamyine, the Indian immigrants formed a majority of the population. The Burmese under the British rule felt helpless, and reacted with a "racism that combined feelings of superiority and fear."[61]

The impact of immigration was particularly acute in Arakan, one of less populated regions. The Rakine saw themselves as made a minority in their own land by Indian immigration with complaints being made all of the jobs and land were going to the Rohingyas.[62] In 1939, the British authorities, alert to the long-term animosity between the Rakhine Buddhists and the Muslims, formed a special Investigation Commission led by James Ester and Tin Tut to study the issue of Muslim immigration into the Arakan. The commission recommended securing the border; however, with the onset of World War II, the British retreated from Arakan.[63]

World War II Japanese occupation and inter-communal violence

During World War II, the Imperial Japanese Army invaded British-controlled Burma. The British forces retreated and in the power vacuum left behind, considerable inter communal violence erupted between Arakanese and Muslim villagers. The British armed Muslims in northern Arakan in order to create a buffer zone that would protect the region from a Japanese invasion when they retreated[64] and to counteract the largely pro-Japanese ethnic Rakhines.[45] The period also witnessed violence between groups loyal to the British and the Burmese nationalists.[64]

Aye Chan, a historian at the Kanda University, has written that as a consequence of acquiring arms from the British during World War II, Rohingyas[note 1] tried to destroy the Arakanese villages instead of resisting the Japanese. In March 1942, Rohingyas from northern Arakan killed around 20,000 Arakanese. In return, around 5,000 Muslims in the Minbya and Mrauk-U Townships were killed by Rakhines and Red Karens.[63]

As in the rest of Burma, the Japanese committed acts of rape, murder and torture against Muslims in Arakan.[65] During this period, some 22,000 Muslims in Arakan were believed to have crossed the border into Bengal, then part of British India, to escape the violence.[66][67][68] The exodus was not restricted to Muslims in Arakan. Thousands of Burmese Indians, Anglo-Burmese and British who settled during colonial period emigrated en masse to India.

To facilitate their reentry into Burma, British formed Volunteer Forces with Rohingya. Over the three years during which the Allies and Japanese fought over the Mayu peninsula, the Rohingya recruits of the V-Force, engaged in a campaign against Arakanese communities, using weapons provided by V-Force.[31] According to the secretary of British governor, the V Force, instead of fighting the Japanese, destroyed Buddhist monasteries, pagodas, and houses, and committed atrocities in northern Arakan.[69][70]

Pakistan Movement and Post-war insurgency

In 1948, when Burma became independent of Great Britain, the Burmese government refused to recognize the Rohingyas as Burmese citizens.[62] The Rakhine for their part felt discriminated against by the governments in Rangoon dominated by the ethnic Burmese with one Rakhine politician saying “we are therefore the victims of Muslimisation and Burmese chauvinism”.[62] The Economist wrote in 2015 that from the 1940s on and right to this day, the Burmens have seen and see themselves as victims of the British Empire while the Rakhine see themselves as victims of the British and the Burmens; both groups were and are so intent upon seeing themselves as victims that neither has much sympathy for the Rohingyas.[62]

During the Pakistan Movement in the 1940s, Rohingya Muslims in western Burma organized a separatist movement to merge the region into East Pakistan.[58] Before the independence of Burma in January 1948, Muslim leaders from Arakan addressed themselves to Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan, and asked his assistance in incorporating the Mayu region to Pakistan considering their religious affinity and geographical proximity with East Pakistan.[58]Two months later, the north Arakan Muslim League was founded in Akyab (modern Sittwe). It demanded annexation to Pakistan.[58] The proposal was never materialized since it was reportedly turned down by Jinnah saying that he was not in a position to interfere into Burmese matters.[58]

After Jinnah's refusal, Rohingya elders who supported a jihad movement, founded the Mujahid party in northern Arakan in 1947.[71] The aim of the Mujahid party was to create an autonomous Muslim state in Arakan. By the 1950s, they began to use the term "Rohingya" which may be a continuation of the term Rooinga to establish a distinct identity and identify themselves as indigenous. They were much more active before the 1962 Burmese coup d'état by General Ne Win, a Burmese general who began his military career fighting for the Japanese in World War II. Ne Win carried out military operations against them over a period of two decades. The prominent one was Operation King Dragon, which took place in 1978; as a result, many Muslims in the region fled to neighboring Bangladesh as refugees. In addition to Bangladesh, a large number of Rohingyas also migrated to Karachi, Pakistan.[13]Rohingya mujahideen are still active within the remote areas of Arakan.[72]

Post-independence immigration and Bangladesh Liberation War

The numbers and the extent of post-independence immigration from Bangladesh are subject to controversy and debate. In a 1955 study published by Stanford University, the authors Virginia Thompson and Richard Adloff write, "The post-war (World War II) illegal immigration of Chittagonians into that area was on a vast scale, and in the Maungdaw and Buthidaung areas they replaced the Arakanese."[27] The authors further argue that the term Rohingya, in the form of Rwangya, first appeared to distinguish settled population from newcomers: "The newcomers were called Mujahids (crusaders), in contrast to the Rwangya or settled Chittagonian population."[27] According to ICG, The International Crisis Group, these immigrants were actually the Rohingyas who were displaced by the World War II and began to return to Arakan after the independence of Burma but were rendered as illegal immigrants, while many were not allowed to return.[37]ICG adds that there were "some 17,000" refugees from the Bangladesh liberation war who "subsequently returned home".[37]

From 1971 to 1978, a number of Rakhine monks and Buddhists staged hunger strikes in Sittwe to force the government to tackle immigration issues which they believed to be causing a demographic shift in the region.[73] Ne Win's government requested UN to repatriate the war refugees and launched military operations which drove off around 200,000 people to Bangladesh. In 1978, the Bangladesh government protested against the Burmese government concerning "the expulsion by force of thousands of Burmese Muslim citizens to Bangladesh." The Burmese government responded that those expelled were Bangladesh citizens who had resided illegally in Burma. In July 1978, after intensive negotiations mediated by UN, Ne Win's government agreed to take back 200,000 refugees who settled in Arakan.[74] In the same year as well as in 1992, a joint statement by governments of Myanmar and Bangladesh "acknowledged that the Rohingya were lawful Burmese residents".[75] In 1982, the Burmese government enacted the citizenship law and declared the "Bengalis" are foreigners.[76]

There are widespread beliefs among Rakhine people that significant number of immigrants arrived even after the 1980s when the border was relatively unguarded. However, there is no documentation proof for these claims as the last census was conducted in 1983.[5] Successive Burmese governments have fortified the border and built up border guard forces.

'Rohingya' movement (1990–present)

"Rohingyas have been in Rakhine from the creation of the world. Arakan was ours; it was an Indian land for 1,000 years."

— Kyaw Min, Yangon-based Rohingya politician[77]

Since the 1990s, a new 'Rohingya' movement which is distinct from the 1950s armed rebellion has emerged. The new movement is characterized by lobbying internationally by overseas diaspora, establishing indigenous claims by Rohingya scholars, publicizing the term "Rohingya" and denying Bengali origins by Rohingya politicians.[29]

Rohingya scholars have claimed that Rakhine was previously a Muslim state for a millennium, or that Muslims were king-makers of Rakhine kings for 350 years. They often traced the origin of Rohingyas to Arab seafarers. These claims have been rejected as "newly invented myths" in academic circles.[42] Some Rohingya politicians have labelled Burmese and international historians as "Rakhine sympathizers" for rejecting the purported historical origins.[78] Nonetheless, the term spreads with great success after the riots in 2012.

The movement has garnered sharp criticisms from ethnic Rakhines and Kamans, the latter of whom are a recognized Muslim ethnic group in Rakhine. Kaman leaders support citizenship for Muslims in northern Rakhine but believe that the new movement is aimed at achieving a self-administered area or Rohang State as a separate Muslim state carved out of Rakhine and condemn the movement.[79]

Rakhines' views are more critical. Citing Bangladesh's overpopulation and density, Rakhines perceive the Rohingyas as "the vanguard of an unstoppable wave of people that will inevitably engulf Rakhine."[80] However, for moderate Rohingyas, the aim may have been no more than to gain citizenship status. Moderate Rohingya politicians agree to compromise on the term Rohingya if citizenship is provided under an alternative identity that is neither "Bengali" nor "Rohingya". Various alternatives including "Rakhine Muslims", "Myanmar Muslims" or simply "Myanmar" have been proposed.[24][81]

Burmese juntas (1990–2011)

The military junta that ruled Myanmar for half a century relied heavily on mixing Burmese nationalism and Theravada Buddhism to bolster its rule, and, in the view of the US government, heavily discriminated against minorities like the Rohingyas and the Chinese people in Myanmar such as the Kokangs and Panthays. Some pro-democracy dissidents from Myanmar's ethnic Bamar majority do not consider the Rohingyas compatriots.[82][83][84][85]

Successive Burmese governments have been accused of provoking riots led by Buddhist monks against ethnic minorities like the Rohingyas and Chinese.[86] In 2009, a senior Burmese envoy to Hong Kong branded the Rohingyas "ugly as ogres" and a people that are alien to Myanmar.[87][88]

Rakhine State riots and refugee crisis (2012–present)

The 2012 Rakhine State riots were a series of conflicts between Rohingya Muslims who are majority in the northern Rakhine and ethnic Rakhines who are majority in the south. Before the riots, there were widespread and strongly held fears circulating among Buddhist Rakhines that they would soon become a minority in their ancestral state.[80] The riots finally came after weeks of sectarian disputes including a gang rape and murder of a Rakhine woman by Rohingyas and killing of ten Burmese Muslims by Rakhines.[89][90] There is evidence that the pogroms in 2012 were organized with Rakhine men who participated in the riots telling International State Crime Initiative (ISCI) that they were told by the government to defend their “race and religion”, were given knives and free food and were bused in from Sittwe to attack the Rohingyas.[62] The Burmese government denies having organized the pogroms, but to date has never prosecuted anyone for the attacks against the Rohingyas.[62] The Economist argued that since the transition to democracy began in Burma in 2011, the military has been seeking to keep its privileged position, and wanted to encourage riots in 2012 so that the military can pose to the public as the defender of Buddhism against the Muslim Rohingya.[62]

From both sides, whole villages were "decimated".[90][91] According to the Burmese authorities, the violence, between ethnic Rakhine Buddhists and Rohingya Muslims, left 78 people dead, 87 injured, and up to 140,000 people have been displaced.[92][93] The government has responded by imposing curfews and by deploying troops in the region. On 10 June 2012, a state of emergency was declared in Rakhine, allowing the military to participate in the administration of the region.[94][95] Rohingya NGOs overseas have accused the Burmese army and police of targeting Rohingya Muslims through arrests and participating in violence.[92][96]

However, a field observation conducted by the International Crisis Group states that both communities were grateful for the protection provided by the military.[97] A number of monks' organisations have taken measures to boycott NGOs which they believe helped only Rohingyas in the past decades even though Rakhines are equally poor.[98] In July 2012, the Burmese Government did not include the Rohingya minority group in the census—classified as stateless Bengali Muslims from Bangladesh since 1982.[99] About 140,000 Rohingya in Myanmar remain confined in IDP camps.[35]

In 2015, the Simon-Skjodt Centre of America’s Holocaust Memorial Museum stated in a press statement the Rohingyas are "at grave risk of additional mass atrocities and even genocide".[62] In 2015, to escape violence and persecution, thousands of Rohingyas migrated from Myanmar and Bangladesh, collectively dubbed as 'boat people' by international media,[100] to Southeast Asian countries including Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand by rickety boats via the waters of the Strait of Malacca and the Andaman Sea.[100][101][102][103] The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees estimates about 25,000 people have been taken to boats from January to March in 2015.[104][105] There are claims that around 100 people died in Indonesia,[106] 200 in Malaysia,[107] and 10 in Thailand[108] during the journey. An estimated 3,000 refugees from Myanmar and Bangladesh have been rescued or swum to shore and several thousand more are believed to remain trapped on boats at sea with little food or water. A Malaysian newspaper claimed crisis has been sparked by smugglers.[109] However, the Economist in an article in June 2015 wrote the only reason why the Rohingyas were willing to pay to be taken out of Burma in squalid, overcrowded, fetid boats as "...it is the terrible conditions at home in Rakhine that force the Rohingyas out to sea in the first place.".[62]

In late 2016, the Myanmar military forces and extremist Buddhists started a major crackdown on the Rohingya Muslims in the country's western region of Rakhine State. The crackdown was in response to attacks on border police camps by unidentified insurgents,[110] and has resulted in wide-scale human rights violations at the hands of security forces, including extrajudicial killings, gang rapes, arsons, and other brutalities.[111][112][113] The military crackdown on Rohingya people drew criticism from various quarters including the United Nations, human rights group Amnesty International, the US Department of State, and the government of Malaysia.[114][115][116][117][118] The de facto head of government Aung San Suu Kyi has particularly been criticized for her inaction and silence over the issue and for not doing much to prevent military abuses.[111][112][3]

In January 2016, the government of Bangladesh initiated a plan to relocate tens of thousands of Rohingya refugees, who had fled to the country following persecution in Myanmar.[119][120] The refugees are to be relocated to the island of Thengar Char.[119][120] The move has received substantial opposition. Human rights groups have seen the plan as a forced relocation.[119][120] Additionally, concerns have been raised about living conditions on the island, which is low-lying and prone to flooding.[119][120] The island has been described as "only accessible during winter and a haven for pirates".[119][120] It is nine hours away from the camps in which the Rohingya currently live.[119][120] 65,000 refugees have been estimated to have entered Bangladesh since October 2016: more than 200,000 are estimated to have been there already.[119][120]

Historical demographics

The following table shows the statistics of Muslim population in Arakan. Note that except for 2014 census, the data is for all Muslims in Rakhine. The data for Burmese 1802 census is taken from a book by J. S. Furnivall. The British censuses classified immigrants from Chittagong as Bengalis. There were a small number of immigrants from other parts of India. The 1941 census was lost during the war. The 1983 census conducted under the Ne Win's government omitted people in volatile regions. It is unclear how many were missed. British era censuses can be found at Digital Library of India.

| Year | Muslims

in Arakan

| Muslims in

Akyub

District

| Akyub's

population

| Percentage

of Muslims

in Akyub

| Indians in Arakan

(Including most

Muslims)

| Indians born

outside Myanmar

| Arakan's total

population

| Percentage of Muslims

in Arakan

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1802 census

(Burmese)

| Lost? | 248,604 | ~1-2% (estimate) | |||||

| 1869 | 24,637 | 10% | 447,957 | 5% | ||||

| 1872 census | 64,315 | 58,255 | 276,671 | 21% | 484,963 | 13% | ||

| 1881 census | 359,706 | 113,557 | 71,104 | 588,690 | ||||

| 1891 census | 416,305 | 137,922 | 62,844 | 673,274 | ||||

| 1901 census | 162,754 | 154,887 | 481,666 | 32% | 173,884 | 76,445 | 762,102 | 21% |

| 1911 census | 178,647 | 529,943 | 30% | 197,990 | 46,591 | 839,896 | ||

| 1921 census | 576,430 | 206,990 | 51,825 | 909,246 | ||||

| 1931 census | 255,469 | 242,381 | 637,580 | 38% | 217,801 | 50,565 | 1,008,535 | 25.3% |

| 1983 census | 584,518 | 2,045,559 | 29% | |||||

| 2014 census

estimate

| 1.3 million[4]

(+1 million overseas)

| 3,188,963 | 40% (~60% if overseas population is included.) |

Demographics

Those who identify as Rohingyas typically reside in the northernmost townships of Arakan bordering Bangladesh where they form 80–98% of the population. A typical Rohingya family has four or five surviving children but the numbers up to twenty eight have been recorded in rare cases.[5][121] Rohingyas have 46 % more children than Myanmar's national average.[5] As of 2014, about 1.3 million Rohingyas live in Myanmar and an estimated 1 million overseas. They form 40% of Rakhine State's population or 60% if overseas population is included. As of December 2016, 1 in 7 stateless persons worldwide are Rohingya per United Nationsfigures.[1]

Language

The Rohingya language is part of the Indo-Aryan sub-branch of the greater Indo-European language family and is related to the Chittagonian language spoken in the southernmost part of Bangladesh bordering Myanmar.[21] While both Rohingya and Chittagonian are related to Bengali, they are not mutually intelligible with the latter. Rohingyas do not speak Burmese, the lingua franca of Myanmar, and face problems in integration. Rohingya scholars have successfully written the Rohingya language in various scripts including the Arabic, Hanifi, Urdu, Roman, and Burmese alphabets, where Hanifi is a newly developed alphabet derived from Arabic with the addition of four characters from Latin and Burmese.

More recently, a Latin alphabet has been developed using all 26 English letters A to Z and two additional Latin letters Ç (for retroflex R) and Ñ (for nasal sound). To accurately represent Rohingya phonology, it also uses five accented vowels (áéíóú). It has been recognised by ISO with ISO 639-3 "rhg" code.[122]

Religion

The Rohingya people practice Sunni Islam along with elements of Sufism. The government restricts educational opportunities for them, many pursue fundamental Islamic studies as their only educational option. Mosques and madrasasare present in most villages. Traditionally, men pray in congregations and women pray at home.

Health

The Rohingya face discrimination and barriers to health care.[1][123] According to a 2016 study published in the medical journal The Lancet, Rohingya children in Myanmar face low birth weight, malnutrition, diarrhea, and barriers to reproduction on reaching adulthood.[1] Rohingya have a child mortality rate of up to 224 deaths per 1000 live births, more than 4 times the rate for the rest of Myanmar (52 per 1000 live births), and 3 times rate of rest non-Rohingya areas of Rakhine state (77 per 1000 live births).[124] The paper also found that 40% of Rohingya children suffer from diarrhea in internally displaced persons camp within Myanmar at a rate five times that of diarrheal illness among children in the rest of Rakhine.[124]

Human rights and refugee status

The Rohingyas’ freedom of movement is severely restricted and the vast majority of them have effectively been denied Burmese citizenship. They are also subjected to various forms of extortion and arbitrary taxation; land confiscation; forced eviction and house destruction; and financial restrictions on marriage.

—Amnesty International in 2004[125]

The Rohingya people have been described as "amongst the world's least wanted and "one of the world's most persecuted minorities.""[126][127] The Rohingya are deprived of the right to free movement and of higher education.[128] They have been denied Burmese citizenship since the Burmese nationality law was enacted.[129] They are not allowed to travel without official permission and were previously required to sign a commitment not to have more than two children, though the law was not strictly enforced. They are subjected to routine forced labour, typically a Rohingya man will have to give up one day a week to work on military or government projects, and one night for sentry duty. The Rohingya have also lost a lot of arable land, which has been confiscated by the military to give to Buddhist settlers from elsewhere in Myanmar.[130][129]

According to Amnesty International, the Rohingya have suffered from human rights violations under the military dictatorship since 1978, and many have fled to neighbouring Bangladesh as a result.[125] In 2005, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees had assisted with the repatriation of Rohingyas from Bangladesh, but allegations of human rights abuses in the refugee camps threatened this effort.[131] In 2015, 140,000 Rohingyas remain in IDP camps after communal riots in 2012.[132] Despite earlier efforts by the UN, the vast majority of Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh are unable to return because of the 2012 communal violence and fear of persecution. Bangladeshi government has reduced the amount of support for Rohingyas to prevent an outflow of refugees to Bangladesh.[133] In February 2009, many Rohingya refugees were rescued by Acehnesesailors in the Strait of Malacca, after 21 days at sea.[134]

The Rakhine community as a whole has tended to be cast internationally as violent extremists – ignoring the diversity of opinions that exist, the fact that the Rakhine themselves are a long-oppressed minority, and rarely attempting to understand their perspective and concerns. This is counterproductive: it promotes a siege mentality on the part of the Rakhine, and obscures complex realities that must be understood if a sustainable way forward is to be found.

—The International Crisis Group, The Politics of Rakhine State, 22 October 2014[37]

Thousands of Rohingyas have also fled to Thailand. There have been charges that Rohingyas were shipped and towed out to open sea from Thailand. In February 2009, evidence of the Thai army towing a boatload of 190 Rohingya refugees out to sea has surfaced. A group of refugees rescued by Indonesian authorities told that they were captured and beaten by the Thai military, and then abandoned at sea.[135]

Steps to repatriate Rohingya refugees began in 2005. In 2009, the government of Bangladesh announced that it will repatriate around 9,000 Rohingyas living in refugee camps inside the country back to Myanmar, after a meeting with Burmese diplomats.[136][137] On 16 October 2011, the new government of Myanmar agreed to take back registered Rohingya refugees. However, Rakhine State riots in 2012 hampered the repatriation efforts.[138][139]

On 29 March 2014, the Burmese government banned the word "Rohingya" and asked for registration of the minority as "Bengalis" in the 2014 Myanmar Census, the first in three decades.[140][141] On 7 May 2014, the United States House of Representatives passed the United States House resolution on persecution of the Rohingya people in Burma that called on the government of Myanmar to end the discrimination and persecution.[142][143] Researchers from the International State Crime Initiative at Queen Mary University of London suggest that the Myanmar government are in the final stages of an organised process of genocide against the Rohingya.[144][145] In November 2016, a senior UN official in Bangladesh accused Myanmar of ethnic cleansing of Rohingyas.[112] However, such viewpoints have been criticized for using loaded terms to gain megaphone attention. Mr Charles Petrie, a former top UN official in Myanmar, argues that "Today using the term, aside from being divisive and potentially incorrect, will only ensure that opportunities and options to try to resolve the issue to be addressed will not be available."[45][146]