Medicine From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia & Alternative medicine From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia and Traditional medicine From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to navigationJump to search hideThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages) This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: Includes many primary sources and debunked pseudoscience masquerading as science. (May 2018) This article needs more medical references for verification or relies too heavily on primary sources. (May 2018) This article is part of a series on Alternative medicine, pseudomedicine and medical conspiracy theories Outline-body-aura.svg General information[hide] Alternative medicine Quackery (Health fraud) History of alternative medicine Rise of modern medicine Pseudoscience Pseudomedicine Antiscience Skepticism Skeptical movement Fringe medicine and science[hide] Accupressure Acupuncture Anthroposophic medicine Bonesetter Chiropractic Homeopathy Mesmerism Naturopathy Orgone Osteopathy Parapsychology Phrenology Radionics Conspiracy theories[hide] Big Pharma conspiracy theory Anti-fluoridation movement Anti-vaccine movement Vaccines causing autism GMO conspiracy theories HIV/AIDS origins Chemtrails Classifications[hide] Alternative medical systems Mind–body intervention Biologically-based therapy Manipulative methods Energy therapy Traditional medicine[hide] Apitherapy Ayurveda African Greek Roman European Japanese Shamanism Siddha Chinese Korean Mongolian Tibetan Yunani Chumash v t e Traditional medicine in a market in Antananarivo, Madagascar Botánicas such as this one in Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts, cater to the Latino community and sell folk medicine alongside statues of saints, candles decorated with prayers, lucky bamboo, and other items. Traditional medicine (also known as indigenous or folk medicine) comprises medical aspects of traditional knowledge that developed over generations within various societies before the era of modern medicine. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines traditional medicine as "the sum total of the knowledge, skills, and practices based on the theories, beliefs, and experiences indigenous to different cultures, whether explicable or not, used in the maintenance of health as well as in the prevention, diagnosis, improvement or treatment of physical and mental illness".[1] In some Asian and African countries, up to 80% of the population relies on traditional medicine for their primary health care needs. When adopted outside its traditional culture, traditional medicine is often considered a form of alternative medicine.[1] Practices known as traditional medicines include Traditional European Medicine (TEM), Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), traditional Korean medicine (TKM), traditional African medicine, (TAM), Ayurveda, Siddha medicine, Unani, ancient Iranian medicine, Iranian (Persian), Islamic medicine, Muti, and Ifá. Scientific disciplines which study traditional medicine include herbalism, ethnomedicine, ethnobotany, and medical anthropology. The WHO notes, however, that "inappropriate use of traditional medicines or practices can have negative or dangerous effects" and that "further research is needed to ascertain the efficacy and safety" of several of the practices and medicinal plants used by traditional medicine systems.[1] The line between alternative medicine and quackery, alternative medicine or fraud is complex and context dependant. Contents [hide] 1 Usage and history 1.1 Classical history 1.2 Medieval and later 1.3 Colonial America 1.4 Modern usage 2 Knowledge transmission and creation 3 Definition and terminology 3.1 Folk medicine 3.2 Home remedies 4 Criticism 4.1 Safety concerns 4.2 Use of endangered species 5 See also 6 References 7 External links Usage and history[edit] Classical history[edit] Further information: Medicine in ancient Greece and Medicine in ancient Rome In the written record, the study of herbs dates back 5,000 years to the ancient Sumerians, who described well-established medicinal uses for plants. In Ancient Egyptian medicine, the Ebers papyrus from c. 1552 BC records a list of folk remedies and magical medical practices.[2] The Old Testament also mentions herb use and cultivation in regards to Kashrut. Many herbs and minerals used in Ayurveda were described by ancient Indian herbalists such as Charaka and Sushruta during the 1st millennium BC.[3] The first Chinese herbal book was the Shennong Bencao Jing, compiled during the Han Dynasty but dating back to a much earlier date, which was later augmented as the Yaoxing Lun (Treatise on the Nature of Medicinal Herbs) during the Tang Dynasty. Early recognised Greek compilers of existing and current herbal knowledge include Pythagoras and his followers, Hippocrates, Aristotle, Theophrastus, Dioscorides and Galen. Roman sources included Pliny the Elder's Natural History and Celsus's De Medicina.[4] Pedanius Dioscorides drew on and corrected earlier authors for his De Materia Medica, adding much new material; the work was translated into several languages, and Turkish, Arabic and Hebrew names were added to it over the centuries.[5] Latin manuscripts of De Materia Medica were combined with a Latin herbal by Apuleius Platonicus (Herbarium Apuleii Platonici) and were incorporated into the Anglo-Saxon codex Cotton Vitellius C.III. These early Greek and Roman compilations became the backbone of European medical theory and were translated by the Persian Avicenna (Ibn Sīnā, 980–1037), the Persian Rhazes (Rāzi, 865–925) and the Jewish Maimonides.[4] Medieval and later[edit] Further information: Medicine in medieval Islam and Medieval medicine of Western Europe Arabic indigenous medicine developed from the conflict between the magic-based medicine of the Bedouins and the Arabic translations of the Hellenic and Ayurvedic medical traditions.[6] Spanish indigenous medicine was influenced by the Arabs from 711 to 1492.[7] Islamic physicians and Muslim botanists such as al-Dinawari[8] and Ibn al-Baitar[9] significantly expanded on the earlier knowledge of materia medica. The most famous Persian medical treatise was Avicenna's The Canon of Medicine, which was an early pharmacopoeia and introduced clinical trials.[10][11][12] The Canon was translated into Latin in the 12th century and remained a medical authority in Europe until the 17th century. The Unani system of traditional medicine is also based on the Canon. Translations of the early Roman-Greek compilations were made into German by Hieronymus Bock whose herbal, published in 1546, was called Kreuter Buch. The book was translated into Dutch as Pemptades by Rembert Dodoens (1517–1585), and from Dutch into English by Carolus Clusius, (1526–1609), published by Henry Lyte in 1578 as A Nievve Herball. This became John Gerard's (1545–1612) Herball or General Hiftorie of Plantes.[4][5] Each new work was a compilation of existing texts with new additions. Women's folk knowledge existed in undocumented parallel with these texts.[4] Forty-four drugs, diluents, flavouring agents and emollients mentioned by Dioscorides are still listed in the official pharmacopoeias of Europe.[5] The Puritans took Gerard's work to the United States where it influenced American Indigenous medicine.[4] Francisco Hernández, physician to Philip II of Spain spent the years 1571–1577 gathering information in Mexico and then wrote Rerum Medicarum Novae Hispaniae Thesaurus, many versions of which have been published including one by Francisco Ximénez. Both Hernandez and Ximenez fitted Aztec ethnomedicinal information into the European concepts of disease such as "warm", "cold", and "moist", but it is not clear that the Aztecs used these categories.[13] Juan de Esteyneffer's Florilegio medicinal de todas las enfermedas compiled European texts and added 35 Mexican plants. Martín de la Cruz wrote an herbal in Nahuatl which was translated into Latin by Juan Badiano as Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis or Codex Barberini, Latin 241 and given to King Carlos V of Spain in 1552.[14] It was apparently written in haste[citation needed] and influenced by the European occupation of the previous 30 years. Fray Bernardino de Sahagún's used ethnographic methods to compile his codices that then became the Historia General de las Cosas de Nueva España, published in 1793.[14] Castore Durante published his Herbario Nuovo in 1585 describing medicinal plants from Europe and the East and West Indies. It was translated into German in 1609 and Italian editions were published for the next century. Colonial America[edit] In 17th and 18th-century America, traditional folk healers, frequently women, used herbal remedies, cupping and leeching.[15] Native American traditional herbal medicine introduced cures for malaria, dysentery, scurvy, non-venereal syphilis, and goiter problems.[16] Many of these herbal and folk remedies continued on through the 19th and into the 20th century,[17] with some plant medicines forming the basis for modern pharmacology.[18][19] Modern usage[edit] At the turn of the 20th century, folk medicine was viewed as a practice used by poverty-stricken communities and quacks. However, synthetic or biomedical products have been questioned by some parts of Western society, allowing for interest in natural medicines. The prevalence of folk medicine in certain areas of the world varies according to cultural norms.[20] Some modern medicine is based on plant phytochemicals that had been used in folk medicine.[21] Researchers state that many of the alternative treatments are "statistically indistinguishable from placebo treatments".[22] Knowledge transmission and creation[edit] Indigenous medicine is generally transmitted orally through a community, family and individuals until "collected". Within a given culture, elements of indigenous medicine knowledge may be diffusely known by many, or may be gathered and applied by those in a specific role of healer such as a shaman or midwife.[23] Three factors legitimize the role of the healer – their own beliefs, the success of their actions and the beliefs of the community. When the claims of indigenous medicine become rejected by a culture, generally three types of adherents still use it – those born and socialized in it who become permanent believers, temporary believers who turn to it in crisis times, and those who only believe in specific aspects, not in all of it.[24][verification needed] Elements in a specific culture are not necessarily integrated into a coherent system, and may be contradictory. In the Caribbean, indigenous remedies fall into several classes: certain well-known European medicinal herbs introduced by the early Spaniard colonists that are still commonly cultivated; indigenous wild and cultivated plants, the uses of which have been adopted from the Amerindians; and ornamental or other plants of relatively recent introduction for which curative uses have been invented without any historical basis.[25][verification needed] Rights of ownership may be claimed in indigenous medical knowledge. Use of such knowledge without Prior Informed Consent of or compensation to those claiming such ownership may be termed 'biopiracy'. See Commercialization of indigenous knowledge, also the Convention on Biological Diversity (in particular Article 8j and the Nagoya Protocol). Definition and terminology[edit] Traditional medicine may sometimes be considered as distinct from folk medicine, and the considered to include formalized aspects of folk medicine. Under this definition folk medicine are longstanding remedies passed on and practised by lay people. Folk medicine consists of the healing practices and ideas of body physiology and health preservation known to some in a culture, transmitted informally as general knowledge, and practiced or applied by anyone in the culture having prior experience.[26] Folk medicine[edit] Curandera performing a limpieza in Cuenca, Ecuador Many countries have practices described as folk medicine which may coexist with formalized, science-based, and institutionalized systems of medical practice represented by conventional medicine.[27] Examples of folk medicine traditions are traditional Chinese medicine, traditional Korean medicine, Arabic indigenous medicine, Uyghur traditional medicine, Japanese Kampō medicine, traditional Aboriginal bush medicine, and Georgian folk medicine, among others.[28] Home remedies[edit] This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (May 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) A home remedy (sometimes also referred to as a granny cure) is a treatment to cure a disease or ailment that employs certain spices, vegetables, or other common items. Home remedies may or may not have medicinal properties that treat or cure the disease or ailment in question, as they are typically passed along by laypersons (which has been facilitated in recent years by the Internet). Many are merely used as a result of tradition or habit or because they are effective in inducing the placebo effect.[29] One of the more popular examples of a home remedy is the use of chicken soup to treat respiratory infections such as a cold or mild flu. Other examples of home remedies include duct tape to help with setting broken bones; and duct tape or superglue to treat plantar warts; and Kogel mogel to treat sore throat. In earlier times, mothers were entrusted with all but serious remedies. Historic cookbooks are frequently full of remedies for dyspepsia, fevers, and female complaints.[30] Components of the aloe vera plant are used to treat skin disorders.[31] Many European liqueurs or digestifs were originally sold as medicinal remedies. In Chinese folk medicine, medicinal congees (long-cooked rice soups with herbs), foods, and soups are part of treatment practices.[32] Criticism[edit] Safety concerns[edit] Although 130 countries have regulations on folk medicines, there are risks associated with the use of them. It is often assumed that because supposed medicines are herbal or natural that they are safe, but numerous precautions are associated with using herbal remedies.[33] Use of endangered species[edit] Sometimes traditional medicines include parts of endangered species, such as the slow loris in Southeast Asia. Endangered animals, such as the Slow loris, are sometimes killed to make traditional medicines.[34] Shark fins have also been used in traditional medicine, and although its use has not been proven, it is hurting shark populations and their ecosystem.[35] See also[edit] Bioprospecting, the commercial exploitation of folk medicinal knowledge Folk healer Herbal medicine Old wives' tale

Dallas Oral Surgery Associates: Specialized Care, Exceptional Service

Welcome and thank you for choosing Dallas Oral Surgery Associates, where Steven Sherry, DDS, MD and John Wallace, DDS, MD provide a full range of solutions – including dental implants, wisdom teeth removal, corrective jaw surgery, and more – to improve your oral and overall health. As a patient of our practice, you’ll receive specialized care performed with an eye for detail and dedication to excellence. Our focus is always on helping you achieve your oral health goals, your comfort and your total well-being.

Safety and Comfort – Our Priorities

Our office is committed to your safety. Our surgical staff are trained in CPR, ACLS (Advanced life support), PALS (Pediatric Life Support), as well as DAANCE (the Dental Anesthesia Assistant National Certification Examination). In addition, our doctors use an amazing array of technology to help you, including 3D CT scans onsite. Our accredited Dallas ambulatory surgery center delivers safety at the stringent, nationally recognized standards of the AAAASF (the American Association for Accreditation of Ambulatory Surgery Facilities). Your comfort is a priority, as we strive to make our office a relaxing, safe, and pleasant environment.

Appointments with Ease

We value your time and pride ourselves on the efficiency of our office. We have convenient office hours, which include some Saturdays, and continue to answer your calls during lunch. This allows you to make appointments that fit your schedule and lifestyle. Once you are a patient, Dr. Sherry and Dr. Wallace are committed to your calls 24/7. They answer your calls after hours, so you always have a direct line to your doctor following your procedure.

You may finance your work through Lending Club or Care Credit, both are leaders in medical and dental financing.

When your general dentist, orthodontist, or medical doctor diagnoses a problem requiring specialized surgical expertise, they call the doctors at Dallas Oral Surgery Associates. Dr. Sherry and Dr. Wallace use their advanced training, experience, and expertise to remedy oral-related problems and deliver positive, predictable results. Patients benefit from experience, exemplary service, and world-class care at Dallas Oral Surgery Associates. Call today to schedule an appointment with Dr. Sherry or Dr. Wallace at our Plano or Dallas office.

Dental Implants

Dental implants are changing the way people live. They are designed to provide a foundation for replacement teeth that look, feel, and function like natural teeth. A person who has lost teeth regains the ability to eat virtually anything, knowing that their teeth appear natural and that their facial contours will be preserved. Patients with dental implants can smile with confidence. Click here to find out more about dental implants.

Wisdom Teeth Removal

Wisdom teeth are the last teeth to erupt within the mouth. When they align properly and gum tissue is healthy, wisdom teeth do not have to be removed. Unfortunately, this does not generally happen. Click here to find out more about wisdom teeth.

Corrective Jaw Surgery

Orthognathic surgery is needed when jaws do not align correctly and/or the teeth do not seem to fit together or function properly. Teeth are straightened with orthodontics and corrective jaw surgery repositions a misaligned jaw. This not only improves facial appearance, but also ensures that teeth meet correctly and function properly. Click here to find out more about corrective jaw surgery.

Medicine

Statue of Asclepius, the Greek god of medicine, holding the symbolic Rod of Asclepius with its coiled serpent

| |

| Specialist | Medical specialty |

|---|---|

| Glossary | Glossary of medicine |

Medicine is the science and practice of the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of disease. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care practices evolved to maintain and restore health by the prevention and treatment of illness. Contemporary medicine applies biomedical sciences, biomedical research, genetics, and medical technology to diagnose, treat, and prevent injury and disease, typically through pharmaceuticals or surgery, but also through therapies as diverse as psychotherapy, external splints and traction, medical devices, biologics, and ionizing radiation, amongst others.[1]

Medicine has existed for thousands of years, during most of which it was an art (an area of skill and knowledge) frequently having connections to the religious and philosophical beliefs of local culture. For example, a medicine man would apply herbs and say prayers for healing, or an ancient philosopher and physician would apply bloodletting according to the theories of humorism. In recent centuries, since the advent of modern science, most medicine has become a combination of art and science (both basic and applied, under the umbrella of medical science). While stitching technique for sutures is an art learned through practice, the knowledge of what happens at the cellular and molecular level in the tissues being stitched arises through science.

Prescientific forms of medicine are now known as traditional medicine and folk medicine. They remain commonly used with or instead of scientific medicine and are thus called alternative medicine. For example, evidence on the effectiveness of acupuncture is "variable and inconsistent" for any condition,[2] but is generally safe when done by an appropriately trained practitioner.[3] In contrast, treatments outside the bounds of safety and efficacy are termed quackery.

Etymology[edit]

Medicine (UK: /ˈmɛdsɪn/ ( listen), US: /ˈmɛdɪsɪn/ (

listen), US: /ˈmɛdɪsɪn/ ( listen)) is the science and practice of the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of disease.[4][5] The word "medicine" is derived from Latin medicus, meaning "a physician".[6][7]

listen)) is the science and practice of the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of disease.[4][5] The word "medicine" is derived from Latin medicus, meaning "a physician".[6][7]

Clinical practice[edit]

Medical availability and clinical practice varies across the world due to regional differences in culture and technology. Modern scientific medicine is highly developed in the Western world, while in developing countries such as parts of Africa or Asia, the population may rely more heavily on traditional medicine with limited evidence and efficacy and no required formal training for practitioners.[8] Even in the developed world however, evidence-based medicine is not universally used in clinical practice; for example, a 2007 survey of literature reviews found that about 49% of the interventions lacked sufficient evidence to support either benefit or harm.[9]

In modern clinical practice, physicians personally assess patients in order to diagnose, treat, and prevent disease using clinical judgment. The doctor-patient relationship typically begins an interaction with an examination of the patient's medical history and medical record, followed by a medical interview[10] and a physical examination. Basic diagnostic medical devices (e.g. stethoscope, tongue depressor) are typically used. After examination for signs and interviewing for symptoms, the doctor may order medical tests (e.g. blood tests), take a biopsy, or prescribe pharmaceutical drugs or other therapies. Differential diagnosis methods help to rule out conditions based on the information provided. During the encounter, properly informing the patient of all relevant facts is an important part of the relationship and the development of trust. The medical encounter is then documented in the medical record, which is a legal document in many jurisdictions.[11] Follow-ups may be shorter but follow the same general procedure, and specialists follow a similar process. The diagnosis and treatment may take only a few minutes or a few weeks depending upon the complexity of the issue.

The components of the medical interview[10] and encounter are:

- Chief complaint (CC): the reason for the current medical visit. These are the 'symptoms.' They are in the patient's own words and are recorded along with the duration of each one. Also called 'chief concern' or 'presenting complaint'.

- History of present illness (HPI): the chronological order of events of symptoms and further clarification of each symptom. Distinguishable from history of previous illness, often called past medical history (PMH). Medical history comprises HPI and PMH.

- Current activity: occupation, hobbies, what the patient actually does.

- Medications (Rx): what drugs the patient takes including prescribed, over-the-counter, and home remedies, as well as alternative and herbal medicines/herbal remedies. Allergies are also recorded.

- Past medical history (PMH/PMHx): concurrent medical problems, past hospitalizations and operations, injuries, past infectious diseases or vaccinations, history of known allergies.

- Social history (SH): birthplace, residences, marital history, social and economic status, habits (including diet, medications, tobacco, alcohol).

- Family history (FH): listing of diseases in the family that may impact the patient. A family tree is sometimes used.

- Review of systems (ROS) or systems inquiry: a set of additional questions to ask, which may be missed on HPI: a general enquiry (have you noticed any weight loss, change in sleep quality, fevers, lumps and bumps? etc.), followed by questions on the body's main organ systems (heart, lungs, digestive tract, urinary tract, etc.).

The physical examination is the examination of the patient for medical signs of disease, which are objective and observable, in contrast to symptoms which are volunteered by the patient and not necessarily objectively observable.[12] The healthcare provider uses the senses of sight, hearing, touch, and sometimes smell (e.g., in infection, uremia, diabetic ketoacidosis). Four actions are the basis of physical examination: inspection, palpation (feel), percussion (tap to determine resonance characteristics), and auscultation (listen), generally in that order although auscultation occurs prior to percussion and palpation for abdominal assessments.[13]

The clinical examination involves the study of:

- Vital signs including height, weight, body temperature, blood pressure, pulse, respiration rate, and hemoglobin oxygen saturation

- General appearance of the patient and specific indicators of disease (nutritional status, presence of jaundice, pallor or clubbing)

- Skin

- Head, eye, ear, nose, and throat (HEENT)

- Cardiovascular (heart and blood vessels)

- Respiratory (large airways and lungs)

- Abdomen and rectum

- Genitalia (and pregnancy if the patient is or could be pregnant)

- Musculoskeletal (including spine and extremities)

- Neurological (consciousness, awareness, brain, vision, cranial nerves, spinal cord and peripheral nerves)

- Psychiatric (orientation, mental state, evidence of abnormal perception or thought).

It is to likely focus on areas of interest highlighted in the medical history and may not include everything listed above.

The treatment plan may include ordering additional medical laboratory tests and medical imaging studies, starting therapy, referral to a specialist, or watchful observation. Follow-up may be advised. Depending upon the health insurance plan and the managed care system, various forms of "utilization review", such as prior authorization of tests, may place barriers on accessing expensive services.[14]

The medical decision-making (MDM) process involves analysis and synthesis of all the above data to come up with a list of possible diagnoses (the differential diagnoses), along with an idea of what needs to be done to obtain a definitive diagnosis that would explain the patient's problem.

On subsequent visits, the process may be repeated in an abbreviated manner to obtain any new history, symptoms, physical findings, and lab or imaging results or specialist consultations.

Institutions[edit]

Contemporary medicine is in general conducted within health care systems. Legal, credentialing and financing frameworks are established by individual governments, augmented on occasion by international organizations, such as churches. The characteristics of any given health care system have significant impact on the way medical care is provided.

From ancient times, Christian emphasis on practical charity gave rise to the development of systematic nursing and hospitals and the Catholic Church today remains the largest non-government provider of medical services in the world.[15] Advanced industrial countries (with the exception of the United States)[16][17] and many developing countries provide medical services through a system of universal health care that aims to guarantee care for all through a single-payer health care system, or compulsory private or co-operative health insurance. This is intended to ensure that the entire population has access to medical care on the basis of need rather than ability to pay. Delivery may be via private medical practices or by state-owned hospitals and clinics, or by charities, most commonly by a combination of all three.

Most tribal societies provide no guarantee of healthcare for the population as a whole. In such societies, healthcare is available to those that can afford to pay for it or have self-insured it (either directly or as part of an employment contract) or who may be covered by care financed by the government or tribe directly.

Transparency of information is another factor defining a delivery system. Access to information on conditions, treatments, quality, and pricing greatly affects the choice by patients/consumers and, therefore, the incentives of medical professionals. While the US healthcare system has come under fire for lack of openness,[18] new legislation may encourage greater openness. There is a perceived tension between the need for transparency on the one hand and such issues as patient confidentiality and the possible exploitation of information for commercial gain on the other.

Delivery[edit]

Provision of medical care is classified into primary, secondary, and tertiary care categories.

Primary care medical services are provided by physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, or other health professionals who have first contact with a patient seeking medical treatment or care. These occur in physician offices, clinics, nursing homes, schools, home visits, and other places close to patients. About 90% of medical visits can be treated by the primary care provider. These include treatment of acute and chronic illnesses, preventive care and health education for all ages and both sexes.

Secondary care medical services are provided by medical specialists in their offices or clinics or at local community hospitals for a patient referred by a primary care provider who first diagnosed or treated the patient. Referrals are made for those patients who required the expertise or procedures performed by specialists. These include both ambulatory care and inpatient services, Emergency departments, intensive care medicine, surgery services, physical therapy, labor and delivery, endoscopy units, diagnostic laboratory and medical imaging services, hospice centers, etc. Some primary care providers may also take care of hospitalized patients and deliver babies in a secondary care setting.

Tertiary care medical services are provided by specialist hospitals or regional centers equipped with diagnostic and treatment facilities not generally available at local hospitals. These include trauma centers, burn treatment centers, advanced neonatology unit services, organ transplants, high-risk pregnancy, radiation oncology, etc.

Modern medical care also depends on information – still delivered in many health care settings on paper records, but increasingly nowadays by electronic means.

In low-income countries, modern healthcare is often too expensive for the average person. International healthcare policy researchers have advocated that "user fees" be removed in these areas to ensure access, although even after removal, significant costs and barriers remain.[19]

Separation of prescribing and dispensing is a practice in medicine and pharmacy in which the physician who provides a medical prescription is independent from thepharmacist who provides the prescription drug. In the Western world there are centuries of tradition for separating pharmacists from physicians. In Asian countries it is traditional for physicians to also provide drugs.[20]

Branches[edit]

Working together as an interdisciplinary team, many highly trained health professionals besides medical practitioners are involved in the delivery of modern health care. Examples include: nurses, emergency medical technicians and paramedics, laboratory scientists, pharmacists, podiatrists, physiotherapists, respiratory therapists, speech therapists, occupational therapists, radiographers, dietitians, and bioengineers, surgeons, surgeon's assistant, surgical technologist.

The scope and sciences underpinning human medicine overlap many other fields. Dentistry, while considered by some a separate discipline from medicine, is a medical field.

A patient admitted to the hospital is usually under the care of a specific team based on their main presenting problem, e.g., the cardiology team, who then may interact with other specialties, e.g., surgical, radiology, to help diagnose or treat the main problem or any subsequent complications/developments.

Physicians have many specializations and subspecializations into certain branches of medicine, which are listed below. There are variations from country to country regarding which specialties certain subspecialties are in.

The main branches of medicine are:

- Basic sciences of medicine; this is what every physician is educated in, and some return to in biomedical research

- Medical specialties

- Interdisciplinary fields, where different medical specialties are mixed to function in certain occasions.

Basic sciences[edit]

- Anatomy is the study of the physical structure of organisms. In contrast to macroscopic or gross anatomy, cytology and histology are concerned with microscopic structures.

- Biochemistry is the study of the chemistry taking place in living organisms, especially the structure and function of their chemical components.

- Biomechanics is the study of the structure and function of biological systems by means of the methods of Mechanics.

- Biostatistics is the application of statistics to biological fields in the broadest sense. A knowledge of biostatistics is essential in the planning, evaluation, and interpretation of medical research. It is also fundamental to epidemiology and evidence-based medicine.

- Biophysics is an interdisciplinary science that uses the methods of physics and physical chemistry to study biological systems.

- Cytology is the microscopic study of individual cells.

- Embryology is the study of the early development of organisms.

- Endocrinology is the study of hormones and their effect throughout the body of animals.

- Epidemiology is the study of the demographics of disease processes, and includes, but is not limited to, the study of epidemics.

- Genetics is the study of genes, and their role in biological inheritance.

- Histology is the study of the structures of biological tissues by light microscopy, electron microscopy and immunohistochemistry.

- Immunology is the study of the immune system, which includes the innate and adaptive immune system in humans, for example.

- Medical physics is the study of the applications of physics principles in medicine.

- Microbiology is the study of microorganisms, including protozoa, bacteria, fungi, and viruses.

- Molecular biology is the study of molecular underpinnings of the process of replication, transcription and translation of the genetic material.

- Neuroscience includes those disciplines of science that are related to the study of the nervous system. A main focus of neuroscience is the biology and physiology of the human brain and spinal cord. Some related clinical specialties include neurology, neurosurgery and psychiatry.

- Nutrition science (theoretical focus) and dietetics (practical focus) is the study of the relationship of food and drink to health and disease, especially in determining an optimal diet. Medical nutrition therapy is done by dietitians and is prescribed for diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, weight and eating disorders, allergies, malnutrition, and neoplastic diseases.

- Pathology as a science is the study of disease—the causes, course, progression and resolution thereof.

- Pharmacology is the study of drugs and their actions.

- Photobiology is the study of the interactions between non-ionizing radiation and living organisms.

- Physiology is the study of the normal functioning of the body and the underlying regulatory mechanisms.

- Radiobiology is the study of the interactions between ionizing radiation and living organisms.

- Toxicology is the study of hazardous effects of drugs and poisons.

Specialties[edit]

In the broadest meaning of "medicine", there are many different specialties. In the UK, most specialities have their own body or college, which have its own entrance examination. These are collectively known as the Royal Colleges, although not all currently use the term "Royal". The development of a speciality is often driven by new technology (such as the development of effective anaesthetics) or ways of working (such as emergency departments); the new specialty leads to the formation of a unifying body of doctors and the prestige of administering their own examination.

Within medical circles, specialities usually fit into one of two broad categories: "Medicine" and "Surgery." "Medicine" refers to the practice of non-operative medicine, and most of its subspecialties require preliminary training in Internal Medicine. In the UK, this was traditionally evidenced by passing the examination for the Membership of the Royal College of Physicians (MRCP) or the equivalent college in Scotland or Ireland. "Surgery" refers to the practice of operative medicine, and most subspecialties in this area require preliminary training in General Surgery, which in the UK leads to membership of the Royal College of Surgeons of England (MRCS). At present, some specialties of medicine do not fit easily into either of these categories, such as radiology, pathology, or anesthesia. Most of these have branched from one or other of the two camps above; for example anaesthesia developed first as a faculty of the Royal College of Surgeons (for which MRCS/FRCS would have been required) before becoming the Royal College of Anaesthetists and membership of the college is attained by sitting for the examination of the Fellowship of the Royal College of Anesthetists (FRCA).

Surgical specialty[edit]

Surgery is an ancient medical specialty that uses operative manual and instrumental techniques on a patient to investigate or treat a pathological condition such as disease or injury, to help improve bodily function or appearance or to repair unwanted ruptured areas (for example, a perforated ear drum). Surgeons must also manage pre-operative, post-operative, and potential surgical candidates on the hospital wards. Surgery has many sub-specialties, including general surgery, ophthalmic surgery, cardiovascular surgery, colorectal surgery, neurosurgery, oral and maxillofacial surgery, oncologic surgery, orthopedic surgery, otolaryngology, plastic surgery, podiatric surgery, transplant surgery, trauma surgery, urology, vascular surgery, and pediatric surgery. In some centers, anesthesiology is part of the division of surgery (for historical and logistical reasons), although it is not a surgical discipline. Other medical specialties may employ surgical procedures, such as ophthalmology and dermatology, but are not considered surgical sub-specialties per se.

Surgical training in the U.S. requires a minimum of five years of residency after medical school. Sub-specialties of surgery often require seven or more years. In addition, fellowships can last an additional one to three years. Because post-residency fellowships can be competitive, many trainees devote two additional years to research. Thus in some cases surgical training will not finish until more than a decade after medical school. Furthermore, surgical training can be very difficult and time-consuming.

Internal specialty[edit]

Internal medicine is the medical specialty dealing with the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of adult diseases. According to some sources, an emphasis on internal structures is implied.[21] In North America, specialists in internal medicine are commonly called "internists." Elsewhere, especially in Commonwealth nations, such specialists are often called physicians.[22] These terms, internist or physician (in the narrow sense, common outside North America), generally exclude practitioners of gynecology and obstetrics, pathology, psychiatry, and especially surgery and its subspecialities.

Because their patients are often seriously ill or require complex investigations, internists do much of their work in hospitals. Formerly, many internists were not subspecialized; such general physicians would see any complex nonsurgical problem; this style of practice has become much less common. In modern urban practice, most internists are subspecialists: that is, they generally limit their medical practice to problems of one organ system or to one particular area of medical knowledge. For example, gastroenterologists and nephrologists specialize respectively in diseases of the gut and the kidneys.[23]

In the Commonwealth of Nations and some other countries, specialist pediatricians and geriatricians are also described as specialist physicians (or internists) who have subspecialized by age of patient rather than by organ system. Elsewhere, especially in North America, general pediatrics is often a form of primary care.

There are many subspecialities (or subdisciplines) of internal medicine:

- Angiology/Vascular Medicine

- Cardiology

- Critical care medicine

- Endocrinology

- Gastroenterology

- Geriatrics

- Hematology

- Hepatology

- Infectious disease

- Nephrology

- Neurology

- Oncology

- Pediatrics

- Pulmonology/Pneumology/Respirology/chest medicine

- Rheumatology

- Sports Medicine

Training in internal medicine (as opposed to surgical training), varies considerably across the world: see the articles on medical education and physician for more details. In North America, it requires at least three years of residency training after medical school, which can then be followed by a one- to three-year fellowship in the subspecialties listed above. In general, resident work hours in medicine are less than those in surgery, averaging about 60 hours per week in the US. This difference does not apply in the UK where all doctors are now required by law to work less than 48 hours per week on average.

Diagnostic specialties[edit]

- Clinical laboratory sciences are the clinical diagnostic services that apply laboratory techniques to diagnosis and management of patients. In the United States, these services are supervised by a pathologist. The personnel that work in these medical laboratory departments are technically trained staff who do not hold medical degrees, but who usually hold an undergraduate medical technology degree, who actually perform the tests, assays, and procedures needed for providing the specific services. Subspecialties include transfusion medicine, cellular pathology, clinical chemistry, hematology, clinical microbiology and clinical immunology.

- Pathology as a medical specialty is the branch of medicine that deals with the study of diseases and the morphologic, physiologic changes produced by them. As a diagnostic specialty, pathology can be considered the basis of modern scientific medical knowledge and plays a large role in evidence-based medicine. Many modern molecular tests such as flow cytometry, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), immunohistochemistry, cytogenetics, gene rearrangements studies and fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) fall within the territory of pathology.

- Diagnostic radiology is concerned with imaging of the body, e.g. by x-rays, x-ray computed tomography, ultrasonography, and nuclear magnetic resonancetomography. Interventional radiologists can access areas in the body under imaging for an intervention or diagnostic sampling.

- Nuclear medicine is concerned with studying human organ systems by administering radiolabelled substances (radiopharmaceuticals) to the body, which can then be imaged outside the body by a gamma camera or a PET scanner. Each radiopharmaceutical consists of two parts: a tracer that is specific for the function under study (e.g., neurotransmitter pathway, metabolic pathway, blood flow, or other), and a radionuclide (usually either a gamma-emitter or a positron emitter). There is a degree of overlap between nuclear medicine and radiology, as evidenced by the emergence of combined devices such as the PET/CT scanner.

- Clinical neurophysiology is concerned with testing the physiology or function of the central and peripheral aspects of the nervous system. These kinds of tests can be divided into recordings of: (1) spontaneous or continuously running electrical activity, or (2) stimulus evoked responses. Subspecialties include electroencephalography, electromyography, evoked potential, nerve conduction study and polysomnography. Sometimes these tests are performed by techs without a medical degree, but the interpretation of these tests is done by a medical professional.

Other major specialties[edit]

The followings are some major medical specialties that do not directly fit into any of the above-mentioned groups:

- Anesthesiology (also known as anaesthetics): concerned with the perioperative management of the surgical patient. The anesthesiologist's role during surgery is to prevent derangement in the vital organs' (i.e. brain, heart, kidneys) functions and postoperative pain. Outside of the operating room, the anesthesiology physician also serves the same function in the labor & delivery ward, and some are specialized in critical medicine.

- Dermatology is concerned with the skin and its diseases. In the UK, dermatology is a subspecialty of general medicine.

- Emergency medicine is concerned with the diagnosis and treatment of acute or life-threatening conditions, including trauma, surgical, medical, pediatric, and psychiatric emergencies.

- Family medicine, family practice, general practice or primary care is, in many countries, the first port-of-call for patients with non-emergency medical problems. Family physicians often provide services across a broad range of settings including office based practices, emergency department coverage, inpatient care, and nursing home care.

- Obstetrics and gynecology (often abbreviated as OB/GYN (American English) or Obs & Gynae (British English)) are concerned respectively with childbirth and the female reproductive and associated organs. Reproductive medicine and fertility medicine are generally practiced by gynecological specialists.

- Medical genetics is concerned with the diagnosis and management of hereditary disorders.

- Neurology is concerned with diseases of the nervous system. In the UK, neurology is a subspecialty of general medicine.

- Ophthalmology is exclusively concerned with the eye and ocular adnexa, combining conservative and surgical therapy.

- Pediatrics (AE) or paediatrics (BE) is devoted to the care of infants, children, and adolescents. Like internal medicine, there are many pediatric subspecialties for specific age ranges, organ systems, disease classes, and sites of care delivery.

- Pharmaceutical medicine is the medical scientific discipline concerned with the discovery, development, evaluation, registration, monitoring and medical aspects of marketing of medicines for the benefit of patients and public health.

- Physical medicine and rehabilitation (or physiatry) is concerned with functional improvement after injury, illness, or congenital disorders.

- Podiatric medicine is the study of, diagnosis, and medical & surgical treatment of disorders of the foot, ankle, lower limb, hip and lower back.

- Psychiatry is the branch of medicine concerned with the bio-psycho-social study of the etiology, diagnosis, treatment and prevention of cognitive, perceptual, emotional and behavioral disorders. Related non-medical fields include psychotherapy and clinical psychology.

- Preventive medicine is the branch of medicine concerned with preventing disease.

- Community health or public health is an aspect of health services concerned with threats to the overall health of a community based on population health analysis.

Alternative medicine

| Alternative medicine | |

|---|---|

| AM, complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), complementary medicine, heterodox medicine, integrative medicine (IM), complementary and integrative medicine (CIM), new-age medicine, unconventional medicine, unorthodox medicine | |

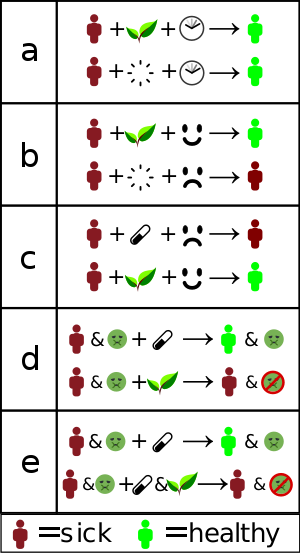

How alternative treatments "work":

a) Misinterpreted natural course – the individual gets better without treatment. b) Placebo effect or false treatment effect – an individual receives "alternative therapy" and is convinced it will help. The conviction makes them more likely to get better. c) Nocebo effect – an individual is convinced that standard treatment will not work, and that alternative treatment will work. This decreases the likelyhood standard treatment will work, while the placebo effect of the "alternative" remains. d) No adverse effects — Standard treatment is replaced with "alternative" treatment, getting rid of adverse effects, but also of improvement. e) Interference — Standard treatment is "complemented" with something that interferes with its effect. This can both cause worse effect, but also decreased (or even increased) side effects, which may be interpreted as "helping". Researchers such as epidemiologists, clinical statisticians and pharmacologists use clinical trials to tease out such effects, allowing doctors to offer only that which has been shown to work. "Alternative treatments" often refuse to use trials or make it deliberately hard to do so. |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Alternative medicine, pseudomedicine and medical conspiracy theories |

|---|

|

Alternative medicine, fringe medicine, pseudomedicine or simply questionable medicine is the use and promotion of practices which are unproven, disproven, impossible to prove, or excessively harmful in relation to their effect — in the attempt to achieve the healing effects of medicine. They differ from experimental medicine in that the latter employs responsible investigation, and accepts results that show it to be ineffective. The scientific consensus is that alternative therapies either do not, or cannot, work. In some cases laws of nature are violated by their basic claims; in some the treatment is so much worse that its use is unethical. Alternative practices, products, and therapies range from only ineffective to having known harmful and toxic effects.

Alternative therapies may be credited for perceived improvement through placebo effects, decreased use or effect of medical treatment (and therefore either decreased side effects; or nocebo effects towards standard treatment), or the natural course of the condition or disease. Alternative treatment is not the same as experimental treatment or traditional medicine, although both can be misused in ways that are alternative. Alternative or complementary medicine is dangerous because it may discourage people from getting the best possible treatment, and may lead to a false understanding of the body and of science.

Alternative medicine is used by a significant number of people, though its popularity is often overstated. Large amounts of funding go to testing alternative medicine, with more than US$2.5 billion spent by the United States government alone. Almost none show any effect beyond that of false treatment, and most studies showing any effect have been statistical flukes. Alternative medicine is a highly profitable industry, with a strong lobby. This fact is often overlooked by media or intentionally kept hidden, with alternative practice being portrayed positively when compared to "big pharma". The lobby has successfully pushed for alternative therapies to be subject to far less regulation than conventional medicine. Alternative therapies may even be allowed to promote use when there is demonstrably no effect, only a tradition of use. Regulation and licensing of alternative medicine and health care providers varies between and within countries. Despite laws making it illegal to market or promote alternative therapies for use in cancer treatment, many practitioners promote them. Alternative medicine is criticized for taking advantage of the weakest members of society. For example, the United States National Institutes of Health department studying alternative medicine, currently named National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, was established as the Office of Alternative Medicine and was renamed the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine before obtaining its current name. Therapies are often framed as "natural" or "holistic", in apparent opposition to conventional medicine which is "artificial" and "narrow in scope", statements which are intentionally misleading. When used together with functional medical treatment, alternative therapies do not "complement" (improve the effect of, or mitigate the side effects of) treatment. Significant drug interactions caused by alternative therapies may instead negatively impact functional treatment, making it less effective, notably in cancer.

Alternative diagnoses and treatments are not part of medicine, or of science-based curricula in medical schools, nor are they used in any practice based on scientific knowledge or experience. Alternative therapies are often based on religious belief, tradition, superstition, belief in supernatural energies, pseudoscience, errors in reasoning, propaganda, fraud, or lies. Alternative medicine is based on misleading statements, quackery, pseudoscience, antiscience, fraud, and poor scientific methodology. Promoting alternative medicine has been called dangerous and unethical. Testing alternative medicine that has no scientific basis has been called a waste of scarce research resources. Critics state that "there is really no such thing as alternative medicine, just medicine that works and medicine that doesn't", that the very idea of "alternative" treatments is paradoxical, as any treatment proven to work is by definition "medicine".

Definitions and terminology[edit]

Alternative medicine[edit]

Alternative medicine is defined loosely as a set of products, practices, and theories that are believed or perceived by their users to have the healing effects of medicine,[n 1][n 2] but whose effectiveness has not been clearly established using scientific methods,[n 1][n 3][4][5][6][7] or whose theory and practice is not part of biomedicine,[n 2][n 4][n 5][n 6] or whose theories or practices are directly contradicted by scientific evidence or scientific principles used in biomedicine.[4][5][11]"Biomedicine" or "medicine" is that part of medical science that applies principles of biology, physiology, molecular biology, biophysics, and other natural sciences to clinical practice, using scientific methods to establish the effectiveness of that practice. Unlike medicine,[n 4] an alternative product or practice does not originate from using scientific methods, but may instead be based on hearsay, religion, tradition, superstition, belief in supernatural energies, pseudoscience, errors in reasoning, propaganda, fraud, or other unscientific sources.[n 3][1][4][5]

In General Guidelines for Methodologies on Research and Evaluation of Traditional Medicine, published in 2000 by the World Health Organization (WHO), complementary and alternative medicine were defined as a broad set of health care practices that are not part of that country's own tradition and are not integrated into the dominant health care system.[12][13]

The expression also refers to a diverse range of related and unrelated products, practices, and theories ranging from biologically plausible practices and products and practices with some evidence, to practices and theories that are directly contradicted by basic science or clear evidence, and products that have been conclusively proven to be ineffective or even toxic and harmful.[n 2][14][15]

The terms alternative medicine, complementary medicine, integrative medicine, holistic medicine, natural medicine, unorthodox medicine, fringe medicine, unconventional medicine, and new age medicine are used interchangeably as having the same meaning and are almost synonymous in some contexts,[16][17][18][19] but may have different meanings in some rare cases.

The meaning of the term "alternative" in the expression "alternative medicine", is not that it is an effective alternative to medical science, although some alternative medicine promoters may use the loose terminology to give the appearance of effectiveness.[4][20] Loose terminology may also be used to suggest meaning that a dichotomy exists when it does not, e.g., the use of the expressions "western medicine" and "eastern medicine" to suggest that the difference is a cultural difference between the Asiatic east and the European west, rather than that the difference is between evidence-based medicine and treatments that don't work.[4]

Complementary or integrative medicine [edit]

Complementary medicine (CM) or integrative medicine (IM) is when alternative medicine is used together with functional medical treatment, in a belief that it improves the effect of treatments.[n 7][1][22][23][24] However, significant drug interactions caused by alternative therapies may instead negatively influence treatment, making treatments less effective, notably cancer therapy.[25][26] Both terms refer to use of alternative medical treatments alongside conventional medicine,[27][28][29] an example of which is use of acupuncture (sticking needles in the body to influence the flow of a supernatural energy), along with using science-based medicine, in the belief that the acupuncture increases the effectiveness or "complements" the science-based medicine.[29]

Allopathic medicine[edit]

Allopathic medicine or allopathy is an expression commonly used by homeopaths and proponents of other forms of alternative medicine to refer to mainstream medicine. It was used to describe the traditional European practice of heroic medicine, which was based on balance of the four "humours" (blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile) where disease was caused by an excess of one humour, and would thus be treated with its opposite.[30] This description continued to be used to describe anything that was not homeopathy.[30] Apart from in India, the term is not used outside alternative medicine and not accepted by the medical field.

Allopathy refers to the use of pharmacologically active agents or physical interventions to treat or suppress symptoms or pathophysiologic processes of diseases or conditions.[31] The German version of the word, allopathisch, was coined in 1810 by the creator of homeopathy, Samuel Hahnemann (1755–1843).[32] The word was coined from allo- (different) and -pathic (relating to a disease or to a method of treatment).[33] In alternative medicine circles the expression "allopathic medicine" is still used to refer to "the broad category of medical practice that is sometimes called Western medicine, biomedicine, evidence-based medicine, or modern medicine" (see the article on scientific medicine).[34]

Use of the term remains common among homeopaths and has spread to other alternative medicine practices. The meaning implied by the label has never been accepted by conventional medicine and is considered pejorative.[35] More recently, some sources have used the term "allopathic", particularly American sources wishing to distinguish between Doctors of Medicine (MD) and Doctors of Osteopathic Medicine (DO) in the United States.[32][36] William Jarvis, an expert on alternative medicine and public health,[37] states that "although many modern therapies can be construed to conform to an allopathic rationale (e.g., using a laxative to relieve constipation), standard medicine has never paid allegiance to an allopathic principle" and that the label "allopath" was from the start "considered highly derisive by regular medicine".[38]

Many conventional medical treatments clearly do not fit the nominal definition of allopathy, as they seek to prevent illness, or remove its cause.[39][40]

CAM[edit]

CAM is an abbreviation of complementary and alternative medicine.[41][42] It has also been called sCAM or SCAM with the addition of "so-called" or "supplements".[43][44] The words balance and holism are often used, claiming to take into account a "whole" person, in contrast to the supposed reductionism of medicine. Due to its many names the field has been criticized for intense rebranding of what are essentially the same practices: as soon as one name is declared synonymous with quackery, a new name is chosen.[16]

Traditional medicine[edit]

Traditional medicine refers to the pre-scientific practices of a certain culture, contrary to what is typically practiced in other cultures where medical science dominates.

"Eastern medicine" typically refers to the traditional medicines of Asia where conventional bio-medicine penetrated much later.

Holistic medicine[edit]

Problems with definition[edit]

Prominent members of the science[45][46] and biomedical science community[3] say that it is not meaningful to define an alternative medicine that is separate from a conventional medicine, that the expressions "conventional medicine", "alternative medicine", "complementary medicine", "integrative medicine", and "holistic medicine" do not refer to any medicine at all.[45][3][46][47]

Others in both the biomedical and CAM communities say that CAM cannot be precisely defined because of the diversity of theories and practices it includes, and because the boundaries between CAM and biomedicine overlap, are porous, and change.[8][48] The expression "complementary and alternative medicine" (CAM) resists easy definition because the health systems and practices it refers to are diffuse, and its boundaries poorly defined.[14][49][n 8] Healthcare practices categorized as alternative may differ in their historical origin, theoretical basis, diagnostic technique, therapeutic practice and in their relationship to the medical mainstream.[51]Some alternative therapies, including traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) and Ayurveda, have antique origins in East or South Asia and are entirely alternative medical systems;[52] others, such as homeopathy and chiropractic, have origins in Europe or the United States and emerged in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.[53]Some, such as osteopathy and chiropractic, employ manipulative physical methods of treatment; others, such as meditation and prayer, are based on mind-body interventions.[54] Treatments considered alternative in one location may be considered conventional in another.[55] Thus, chiropractic is not considered alternative in Denmark and likewise osteopathic medicine is no longer thought of as an alternative therapy in the United States.[55]

Critics say the expression is deceptive because it implies there is an effective alternative to science-based medicine, and that complementary is deceptive because it implies that the treatment increases the effectiveness of (complements) science-based medicine, while alternative medicines that have been tested nearly always have no measurable positive effect compared to a placebo.[4][56][57][58]

Different types of definitions[edit]

One common feature of all definitions of alternative medicine is its designation as "other than" conventional medicine.[59] For example, the widely referenced[60]descriptive definition of complementary and alternative medicine devised by the US National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), states that it is "a group of diverse medical and health care systems, practices, and products that are not generally considered part of conventional medicine".[61] For conventional medical practitioners, it does not necessarily follow that either it or its practitioners would no longer be considered alternative.[n 9]

Some definitions seek to specify alternative medicine in terms of its social and political marginality to mainstream healthcare.[64] This can refer to the lack of support that alternative therapies receive from the medical establishment and related bodies regarding access to research funding, sympathetic coverage in the medical press, or inclusion in the standard medical curriculum.[64] In 1993, the British Medical Association (BMA), one among many professional organizations who have attempted to define alternative medicine, stated that it[n 10] referred to "...those forms of treatment which are not widely used by the conventional healthcare professions, and the skills of which are not taught as part of the undergraduate curriculum of conventional medical and paramedical healthcare courses".[65] In a US context, an influential definition coined in 1993 by the Harvard-based physician,[66] David M. Eisenberg,[67] characterized alternative medicine "as interventions neither taught widely in medical schools nor generally available in US hospitals".[68] These descriptive definitions are inadequate in the present-day when some conventional doctors offer alternative medical treatments and CAM introductory courses or modules can be offered as part of standard undergraduate medical training;[69] alternative medicine is taught in more than 50 per cent of US medical schools and increasingly US health insurers are willing to provide reimbursement for CAM therapies.[70] In 1999, 7.7% of US hospitals reported using some form of CAM therapy; this proportion had risen to 37.7% by 2008.[71]

An expert panel at a conference hosted in 1995 by the US Office for Alternative Medicine (OAM),[72][n 11] devised a theoretical definition[72] of alternative medicine as "a broad domain of healing resources ... other than those intrinsic to the politically dominant health system of a particular society or culture in a given historical period".[74]This definition has been widely adopted by CAM researchers,[72] cited by official government bodies such as the UK Department of Health,[75] attributed as the definition used by the Cochrane Collaboration,[76] and, with some modification,[dubious ] was preferred in the 2005 consensus report of the US Institute of Medicine, Complementary and Alternative Medicine in the United States.[n 2]

The 1995 OAM conference definition, an expansion of Eisenberg's 1993 formulation, is silent regarding questions of the medical effectiveness of alternative therapies.[77] Its proponents hold that it thus avoids relativism about differing forms of medical knowledge and, while it is an essentially political definition, this should not imply that the dominance of mainstream biomedicine is solely due to political forces.[77] According to this definition, alternative and mainstream medicine can only be differentiated with reference to what is "intrinsic to the politically dominant health system of a particular society of culture".[78] However, there is neither a reliable method to distinguish between cultures and subcultures, nor to attribute them as dominant or subordinate, nor any accepted criteria to determine the dominance of a cultural entity.[78] If the culture of a politically dominant healthcare system is held to be equivalent to the perspectives of those charged with the medical management of leading healthcare institutions and programs, the definition fails to recognize the potential for division either within such an elite or between a healthcare elite and the wider population.[78]

Normative definitions distinguish alternative medicine from the biomedical mainstream in its provision of therapies that are unproven, unvalidated, or ineffective and support of theories with no recognized scientific basis.[79] These definitions characterize practices as constituting alternative medicine when, used independently or in place of evidence-based medicine, they are put forward as having the healing effects of medicine, but are not based on evidence gathered with the scientific method.[1][3][27][28][61][80] Exemplifying this perspective, a 1998 editorial co-authored by Marcia Angell, a former editor of The New England Journal of Medicine, argued that:

This line of division has been subject to criticism, however, as not all forms of standard medical practice have adequately demonstrated evidence of benefit,[n 4][81][82]and it is also unlikely in most instances that conventional therapies, if proven to be ineffective, would ever be classified as CAM.[72]

Similarly, the public information website maintained by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of the Commonwealth of Australia uses the acronym "CAM" for a wide range of health care practices, therapies, procedures and devices not within the domain of conventional medicine. In the Australian context this is stated to include acupuncture; aromatherapy; chiropractic; homeopathy; massage; meditation and relaxation therapies; naturopathy; osteopathy; reflexology, traditional Chinese medicine; and the use of vitamin supplements.[83]

The Danish National Board of Health's "Council for Alternative Medicine" (Sundhedsstyrelsens Råd for Alternativ Behandling (SRAB)), an independent institution under the National Board of Health (Danish: Sundhedsstyrelsen), uses the term "alternative medicine" for:

- Treatments performed by therapists that are not authorized healthcare professionals.

- Treatments performed by authorized healthcare professionals, but those based on methods otherwise used mainly outside the healthcare system. People without a healthcare authorisation are [also] allowed to perform the treatments.[84]

Proponents of an evidence-base for medicine[n 12][86][87][88][89] such as the Cochrane Collaboration (founded in 1993 and from 2011 providing input for WHO resolutions) take a position that all systematic reviews of treatments, whether "mainstream" or "alternative", ought to be held to the current standards of scientific method.[90] In a study titled Development and classification of an operational definition of complementary and alternative medicine for the Cochrane Collaboration (2011) it was proposed that indicators that a therapy is accepted include government licensing of practitioners, coverage by health insurance, statements of approval by government agencies, and recommendation as part of a practice guideline; and that if something is currently a standard, accepted therapy, then it is not likely to be widely considered as CAM.[72]

Types[edit]

Alternative medicine consists of a wide range of health care practices, products, and therapies. The shared feature is a claim to heal that is not based on the scientific method. Alternative medicine practices are diverse in their foundations and methodologies.[61] Alternative medicine practices may be classified by their cultural origins or by the types of beliefs upon which they are based.[1][4][11][61] Methods may incorporate or be based on traditional medicinal practices of a particular culture, folk knowledge, superstition,[91] spiritual beliefs, belief in supernatural energies (antiscience), pseudoscience, errors in reasoning, propaganda, fraud, new or different concepts of health and disease, and any bases other than being proven by scientific methods.[1][4][5][11] Different cultures may have their own unique traditional or belief based practices developed recently or over thousands of years, and specific practices or entire systems of practices.

Unscientific belief systems[edit]

Alternative medicine, such as using naturopathy or homeopathy in place of conventional medicine, is based on belief systems not grounded in science.[61]

| Proposed mechanism | Issues | |

|---|---|---|

| Naturopathy | Naturopathic medicine is based on a belief that the body heals itself using a supernatural vital energy that guides bodily processes.[92] | In conflict with the paradigm of evidence-based medicine.[93] Many naturopaths have opposed vaccination,[94] and "scientific evidence does not support claims that naturopathic medicine can cure cancer or any other disease".[95] |

| Homeopathy | A belief that a substance that causes the symptoms of a disease in healthy people cures similar symptoms in sick people.[n 13] | Developed before knowledge of atoms and molecules, or of basic chemistry, which shows that repeated dilution as practiced in homeopathy produces only water, and that homeopathy is not scientifically valid.[97][98][99][100] |

Supplements[edit]

Traditional ethnic systems[edit]

Alternative medical systems may be based on traditional medicine practices, such as traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), Ayurveda in India, or practices of other cultures around the world.[61] Some useful applications of traditional medicines have been researched and accepted within ordinary medicine, however the underlying belief systems are seldom scientific and are not accepted.

Traditional medicine is considered alternative when it is used outside its home region; or when it is used together with or instead of known functional treatment; or when it can be reasonably expected that the patient or practitioner knows or should know that it will not work – such as knowing that the practice is based on superstition.

Since ancient times, in many parts of the world a number of herbs reputed to possess abortifacient properties have been used in folk medicine. Among these are: tansy, pennyroyal, black cohosh, and the now-extinct silphium.[101]:44–47, 62–63, 154–55, 230–31 Historian of science Ann Hibner Koblitz has written of the probable protoscientific origins of this folk knowledge in observation of farm animals. Women who knew that grazing on certain plants would cause an animal to abort (with negative economic consequences for the farm) would be likely to try out those plants on themselves in order to avoid an unwanted pregnancy.[102]:120

However, modern users of these plants often lack knowledge of the proper preparation and dosage. The historian of medicine John Riddle has spoken of the "broken chain of knowledge" caused by urbanization and modernization,[101]:167–205 and Koblitz has written that "folk knowledge about effective contraception techniques often disappears over time or becomes inextricably mixed with useless or harmful practices."[102]:vii The ill-informed or indiscriminant use of herbs as abortifacients can cause serious and even lethal side-effects.[103][104]

| Claims | Issues | |

|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese medicine | Traditional practices and beliefs from China, together with modifications made by the Communist party make up TCM. Common practices include herbal medicine, acupuncture (insertion of needles in the body at specified points), massage (Tui na), exercise (qigong), and dietary therapy. | The practices are based on belief in a supernatural energy called qi, considerations of Chinese Astrology and Chinese numerology, traditional use of herbs and other substances found in China – a belief that the tongue contains a map of the body that reflects changes in the body, and an incorrect model of the anatomy and physiology of internal organs.[4][105][106][107][108][109] |

| Ayurveda | Traditional medicine of India. Ayurveda believes in the existence of three elemental substances, the doshas (called Vata, Pitta and Kapha), and states that a balance of the doshas results in health, while imbalance results in disease. Such disease-inducing imbalances can be adjusted and balanced using traditional herbs, minerals and heavy metals. Ayurveda stresses the use of plant-based medicines and treatments, with some animal products, and added minerals, including sulfur, arsenic, lead and copper sulfate[clarification needed]. | Safety concerns have been raised about Ayurveda, with two U.S. studies finding about 20 percent of Ayurvedic Indian-manufactured patent medicines contained toxic levels of heavy metals such as lead, mercury and arsenic. A 2015 study of users in the United States also found elevated blood lead levels in 40 percent of those tested. Other concerns include the use of herbs containing toxic compounds and the lack of quality control in Ayurvedic facilities. Incidents of heavy metal poisoning have been attributed to the use of these compounds in the United States.[110][111][15][112][113][114][115][116] |

Supernatural energies[edit]

Bases of belief may include belief in existence of supernatural energies undetected by the science of physics, as in biofields, or in belief in properties of the energies of physics that are inconsistent with the laws of physics, as in energy medicine.[61]

| Claims | Issues | |

|---|---|---|

| Biofield therapy | Intended to influence energy fields that, it is purported, surround and penetrate the body.[61] | Writers such as noted astrophysicist and advocate of skeptical thinking (Scientific skepticism) Carl Sagan (1934–1996) have described the lack of empirical evidence to support the existence of the putative energy fields on which these therapies are predicated.[117] |

| Bioelectromagnetictherapy | Use verifiable electromagnetic fields, such as pulsed fields, alternating-current, or direct-current fields in an unconventional manner.[61] | Asserts that magnets can be used to defy the laws of physics to influence health and disease. |

| Chiropractic | Spinal manipulation aims to treat "vertebral subluxations" which are claimed to put pressure on nerves. | Chiropractic was developed in the belief that manipulating the spine affects the flow of a supernatural vital energy and thereby affects health and disease. Vertebral subluxation is a pseudoscientific concept and has not been proven to exist. |

| Reiki | Practitioners place their palms on the patient near Chakras that they believe are centers of supernatural energies in the belief that these supernatural energies can transfer from the practitioner's palms to heal the patient. | Lacks credible scientific evidence.[118] |

Holistic therapy[edit]

| Claims | Issues | |

|---|---|---|

| Mind-body medicine | The mind can affect "bodily functions and symptoms" and there is an interconnection between the mind, body, and spirit. |

Herbal remedies and other substances used[edit]